The Beginning of the End: 8/6/86

Three years after their third World Series victory in 1983, the Orioles completely collapsed. And on the fateful night when the serious losing began, amazingly, they hit two grand slams.

It’s widely believed that the Orioles collapsed pretty much immediately after their World Series triumph in 1983. Within five years, they were making the wrong kind of history by opening a season with 21 straight losses. That’s a fast fall.

But their slide actually wasn’t precipitous at first. As the defending World Series champions in 1984, they posted a winning record. Then they posted another winning record in 1985 — in late September that year, they were a dozen games over .500.

In 1986, with Earl Weaver back as manager and their lineup pounding home runs, they were in second place in the American League East in early August, just two-and-a-half games out of first. Weaver had ended his retirement the year before to take another stab at guiding the Orioles to glory, and given his history of orchestrating late-season surges, his 1986 club looked like it might be playoff material.

That was when the Orioles collapsed — in early August 1986, at the very moment when they appeared capable of big accomplishments. An epic run of losses ensued, with two aspects of their collapse standing out as especially remarkable.

First, while it’s usually foolish to suggest one result in a 162-game season is more pivotal or meaningful than another, the 1986 Orioles clearly were ruined by a single, staggering loss at Memorial Stadium.

And even more remarkable, they hit not one but two grand slams in that ruinous defeat before 19,519 fans on August 6, 1986.

“What a wild game,” recalled then-Orioles broadcaster Jon Miller in his Bird Tapes interview. “That one game started the team on a downward spiral like I’ve never seen from a good team. You can’t be two-and-a-half games out in August unless you’re pretty good.”

The Texas Rangers, the Orioles’ opponents that night at Memorial Stadium, also were contending for the lead in their division, trailing the California Angels by just two-and-a-half games. Both teams needed a win, and the Rangers took an early step toward one when veteran infielder Toby Harrah hit a grand slam off Orioles starter Ken Dixon in the top of the second inning.

The Rangers had a 6-0 lead going into the bottom of the fourth when their starter, Bobby Witt (yes, the father of the Kansas City Royals’ current superstar shortstop), lost command and walked the bases loaded. The Orioles’ Larry Sheets, a 25-year-old outfielder, stepped to the plate. Although he was batting seventh in Weaver’s order, he had plenty of power. He’d hit a home run in each of Baltimore’s prior two games.

Witt tossed Sheets a fastball. Sheets swung and connected, launching a drive that cleared the left-field fence for a grand slam.

The Orioles were back in the game and not done rallying in the bottom of the fourth. Their next batter, Tom O’Malley, singled, sending Witt to the showers, and his replacement, Jeff Russell, fared little better. The bases soon were loaded again with two outs. The rally appeared over when Cal Ripken Jr. hit a ground ball to third, but Rangers third baseman Steve Buechele booted the chance, allowing a run to score and keeping the bases loaded.

Jim Dwyer, the Orioles’ designated hitter, stepped to the plate. He’d drawn a walk earlier in the inning and scored on Sheets’ grand slam. Now, he was back up with the bases loaded.

Dwyer, 36, was a platoon-caliber talent who had forged a long major league career because he could hit. A left-handed batter, he was a dangerous pinch hitter known for being streaky, and that night in Baltimore, he was on a hot streak, having driven in 11 runs in his last eight games. When the Rangers’ Russell grooved a fastball, Dwyer swung and launched a soaring drive that cleared the fence.

“First grand slam, took me 12 years (in the majors) to do it,” Dwyer said later.

Suddenly, it was an historic night. The Orioles had tied a major league record with two grand slams in an inning. And never before in the majors had both teams combined to hit three grand slams in a game. After the game, the Hall of Fame asked for the bats that Harrah, Sheets and Dwyer used to hit their grand slams.

Dwyer’s clout gave the Orioles a 9-6 lead, which grew to 11-6 on a home run by Lee Lacy in the bottom of the sixth. Weaver’s club appeared headed for another win.

But there was a problem. The Orioles’ veteran closer, Don Aase, who’d made the All-Star team that year and led the majors in saves, was unavailable to pitch.

“Earlier that day, he’d been playing with one of his kids and wrenched his back. So he had to be scratched,” Miller recalled.

In the ‘80s, a closer sometimes was asked to handle the final two or three innings of a game, not just the ninth. With Aase out, Weaver turned to Rich Bordi, normally Aase’s set-up man, in the top of the seventh. Bordi retired the Rangers in order in that inning, and with the Orioles well ahead, it was anticipated that he’d also handle the eighth and ninth.

“But Bordi didn’t have it that night,” Miller recalled.

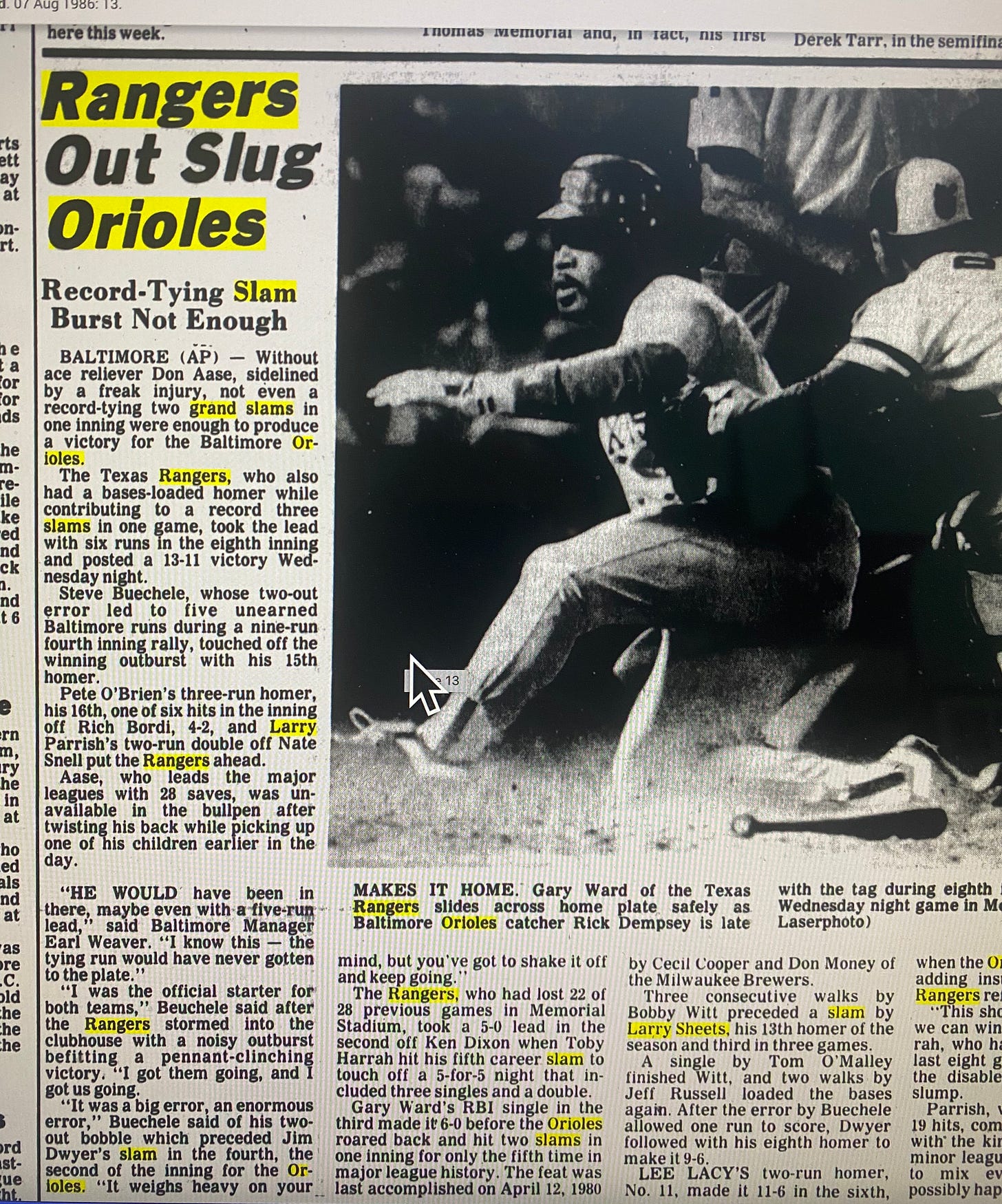

That was an understatement. The Rangers’ Buechele led off the top of the eighth with a home run, and a few batters later, the Rangers’ Pete O’Brien whacked a three-run homer. Suddenly, the Oriole only led by a run, 11-10. Weaver stuck with Bordi until he allowed two more hits, and Bordi’s replacement, Nate Snell, allowed a bases-clearing double that gave the Rangers the lead.

Texas wound up winning, 13-11.

As the Rangers celebrated the improbable comeback win in their clubhouse, Weaver bemoaned Aase’s absence as pivotal. “He would’ve been in there, for sure,” the manager said.

He also sought to downplay the significance of the loss. “It’s just like a 1-0 loss. Look in the paper: one more loss,” Weaver said.

But it was more than just another loss; it was the beginning of his team being revealed for exactly what it was – a deeply flawed squad.

In his Bird Tapes interview, then-Orioles outfielder Fred Lynn said, “We had a bunch of guys who could hit home runs. Hit a ton of home runs. But couldn’t run for beans. No team speed. Ran the bases station to station. None of the pitchers threw hard and they all had control issues at the same time. We couldn’t get off the field defensively. We caught the ball but weren’t very fast. You put all those things together and go, ‘Whoa, things are getting a little dicey here.’”

When they began play on August 6, the Orioles had a 59-47 record. Their loss that night started a five-game losing streak. After they briefly stabilized, winning three of four, they really sank hard, losing 24 of their next 30 games and, overall, 42 of their final 56 to close out the season.

“You can get by with deficiencies on your club for awhile, but the season is long and that’s what happened,” Lynn said.

As the collapse intensified, Weaver lost interest and asked to go home before the end of the season; he knew his managerial career was over, this time for good. Orioles owner Edward Bennett Williams said he could leave but wouldn’t get paid for any games he missed. Weaver stuck around but counted the days until the end of his last season as a major league manager.

“He wasn't used to losing,” Lynn said. “When you’ve won all your life and it becomes hard, that’s tough.”

Weaver also surely recognized that the losing wasn’t going to end anytime soon. The Orioles’ talent well had run dry and their winning era, which dated back to the ‘60s, finally was over — with an exclamation point. Their record after their epic loss on August 6, 1986, made that clear. After they went 14-42 to end that season, they went 67-95 in 1987 and 0-21 to start the 1988 season for an 81-158 overall record and .339 winning percentage during one of the worst stretches in their history.

In hindsight, the date of the game when it all started — 8/6/86 — was especially auspicious. In slang vernacular, to “eighty-six” an item is to lose it, or discard it. The Orioles’ era being contenders definitely was eighty-sixed on 8/6/86.

“It was kind of a Greek tragedy,” Miller said. “They were right there (in the standings) and they had this incredibly wild game that they ended up losing, just a disastrous game. And from that point forward, they lost three-quarters of their games. It was unbelievable.”

I remember that game well. The Orioles' collapse that followed was even a bigger surprise.

PS Today’s 24-2 loss to the Reds could be another of those pivotal games. We’d better get some pitching or we’re dead.