From the Archive: A Final Ride for Curt Blefary's Ashes

During a poignant interview in Florida years ago, the 1965 American League Rookie of the Year told me he’d go to his grave a ballplayer ... and he did.

When I went around the country interviewing former Orioles for my book on the history of the team a quarter-century ago, it wasn’t the first time I’d taken on such an endeavor. Working for the Baltimore Sun in 1986, I wrote a series of articles commemorating the twentieth anniversary of the Orioles’ stunning sweep of the Dodgers in the 1966 World Series. It was quite an assignment. I interviewed Dave McNally at his house in Billings, Montana. I interviewed Wally Bunker at his house off the coast of Washington state. I interviewed Boog Powell at his marina in Key West, Florida. I interviewed Hank Bauer, the Orioles’ manager in 1966, behind home plate during a Royals game in Kansas City, where he worked as a Yankees scout.

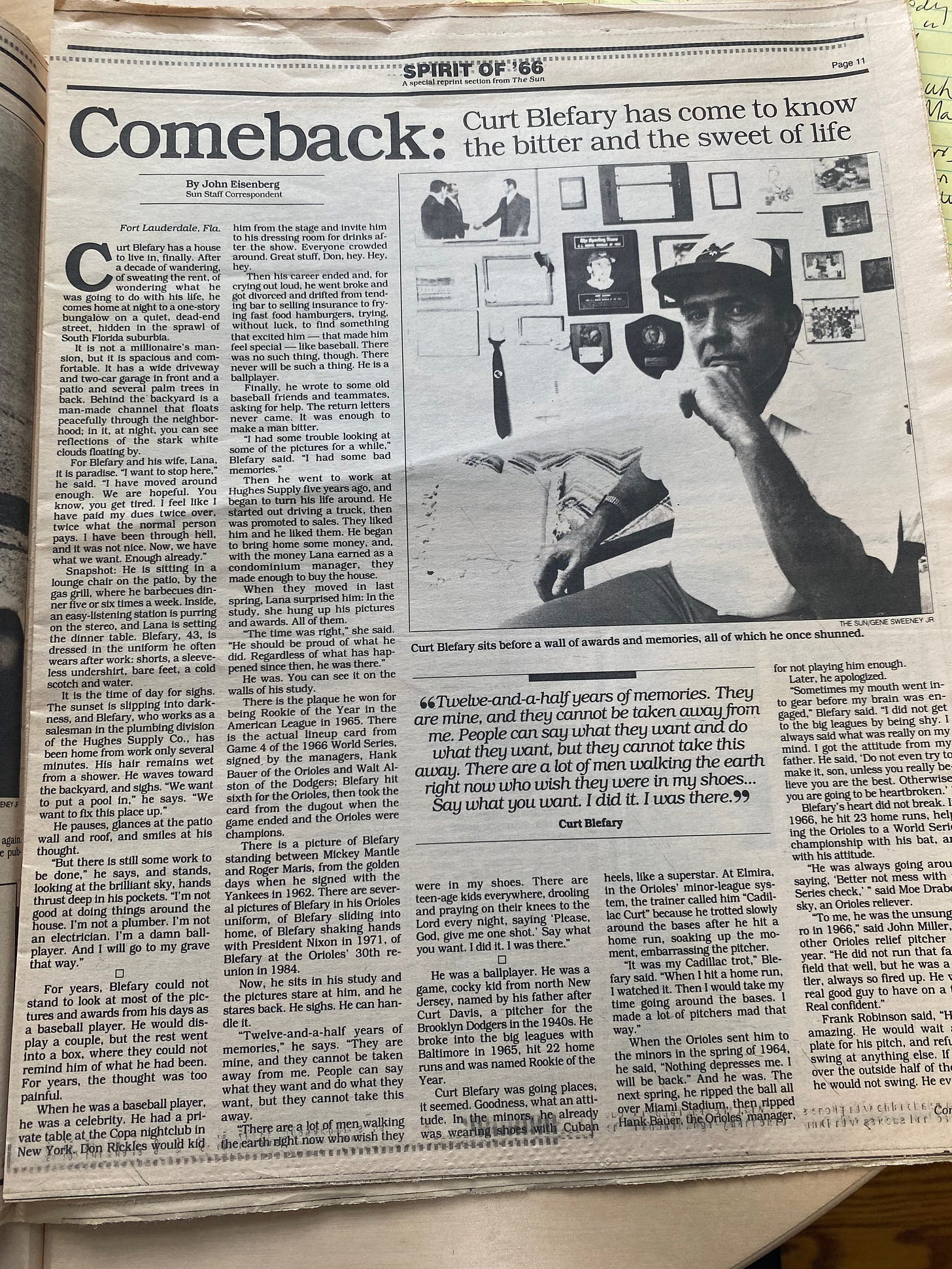

Nearly four decades later, I still vividly recall my interview with Curt Blefary, a feisty New Jersey native who’d played left field and hit 23 home runs for the Orioles in 1966. I’d found him living with his second wife in a tidy house in Fort Lauderdale, Florida. He was a salesman in the plumbing division of a supply company, having worked his way up from driving a truck. He invited me over for dinner, and while he grilled steaks in the backyard, he poured out a tale of woe.

He’d peaked as a player in his first years with the Orioles, winning the American League’s Rookie of the Year award as a 21-year-old in 1965 and continuing to play regularly in 1966 and 1967. He wasn’t a plus fielder — Frank Robinson nicknamed him “Clank” for his iron glove — but he could run and hit for average and power, and he radiated a cocksure attitude, strutting through the clubhouse and admiring his home runs longer than any opposing pitcher wanted.

But he also had a temper, a big mouth and a drinking problem, all of which he readily admitted years later, and when his production waned, he didn’t like being relegated to a part-time role. It was the beginning of a rapid descent.

He irritated Earl Weaver, who became the Orioles’ manager in 1968, and was dealt to the Houston Astros after that season in the trade that brought Mike Cuellar to Baltimore — a lopsided deal if ever there was one. Cuellar would win 143 games for the Orioles over eight seasons, while Blefary lasted just one year in Houston. After a few more stops, his major league career was over before his thirtieth birthday.

(Note: This is a free post. To upgrade to a paid subscription to the Bird Tapes, click on the button below. A paid subscription gives you access to the vintage interviews with former Oriole players and front office executives that are archived at the Bird Tapes.)

When we spoke in his backyard in 1986, Blefary nursed a scotch-and-water and confessed to harboring bitter feelings about baseball. His playing career ended a decade prematurely, he believed. And his outgoing personality and many friends and connections in the sport hadn’t led to a post-playing career as a coach, instructor or scout, which he’d anticipated.

“Evidently I did something wrong to somebody,” he said.

Initially, his post-baseball life had spiraled in the wrong direction in the 1970s as he drifted from tending bar to selling insurance to frying fast-food hamburgers to working as a sheriff. None of it excited him, and after he divorced his first wife, he ran so low on cash one year that he had to bet on a pro football game in hopes of having enough money to give his kids Christmas presents. (The Dallas Cowboys came through for him, he smiled.)

His sister and mother, whom I later interviewed, told me they’d hated seeing Curt, so ebullient as a young ballplayer, become a brooding, bitter ex-player.

He was doing better when we spoke in 1986. He’d worked for the supply company for five years. His new wife, Lana, had a job as a condominium manager and worked hard to buoy his spirits.

But his enduring unease was evident.

“I have everything I could want, a beautiful wife, a beautiful home, a prestigious position. I don’t want for anything, Everything is great. But I still miss baseball,” he lamented.

He knew nothing was going to replace it for him. Gazing at his house while he grilled steaks in the backyard, he said, “We want to fix this place up. But I’m not good at doing things around the house. I’m not a plumber. I’m not an electrician. I’m a damn ballplayer. And I’ll go to my grave that way.”

Shortly after my article on Blefary ran in 1986, casting him as a man whose life was coming together after many struggles, he quit his “prestigious position” to come to Baltimore for the twentieth reunion of the World Series-winning Orioles.

My heart dropped when I heard the news. I feared another downward turn. But if anything, he knew himself … a “damn ballplayer.”

In the years after I wrote about him, Blefary settled into a niche of attending fantasy camps and helping coach a high school team. He self-published a manual on how to play the game. It never stopped bothering him that baseball, his one true love, hadn’t saved him when he needed saving.

Eventually, he developed pancreatitis, a disease that can result from drinking too hard. When he died at age 57 in 2001, Lana told the Associated Press, “It’s good that his suffering is over now.”

A few months later, Lana called the Sun’s sports desk from a campground outside Baltimore. She’d driven up from Florida, staying at campgrounds, with Blefary’s ashes in a shoebox-shaped urn adorned with crossed baseball bats and a ball. He’d told her he wanted his ashes spread at Memorial Stadium, where his best moments in baseball had occurred. But upon arriving in Maryland, she’d discovered that the old stadium was in the process of being demolished. She was looking for help and determined to fulfill his wishes.

“I’m going to get in there one way or another,” she said.

Fortunately, she was met with a groundswell of understanding. The Maryland Stadium Authority, which was overseeing the demolition, allowed her inside the construction zone. The contractor agreed to halt work for a memorial service. The Babe Ruth Museum produced the home plate used at the final game at Memorial Stadium and placed it near where it had been situated during games, Lana secured a hospice minister to oversee a service.

Blefary’s ashes were spread at home plate, or where home plate once resided, on May 24, 2001. He’d told me he’d go to his grave a ballplayer, and sure enough, he did.

I was 16 years old when Curt came to the Orioles! He became one of my favorites during his time with the Orioles!! Enjoyed watching him play!

Hello John. Great story about Curt. I was 9 years old when I saw him in 1966. Had his baseball cards and loved the guy. In the 90s when I did the bird expo at the pikesville armory I had the pleasure to bringing him up from Florida to do a card show. He stayed at our house with my wife and I. He was a gentlemen and great guy. Thank you for the memories and love your material. Regards. Harry Repas.