What Dave McNally's Teammates Really Loved About Him

He was a stubborn competitor on the mound, as his career record indicates. But he was just as stubborn when negotiating his annual salary with the Orioles.

While interviewing former players and team executives for my book on Orioles history a quarter-century ago, it became clear that Dave McNally had been an especially popular figure in the clubhouse.

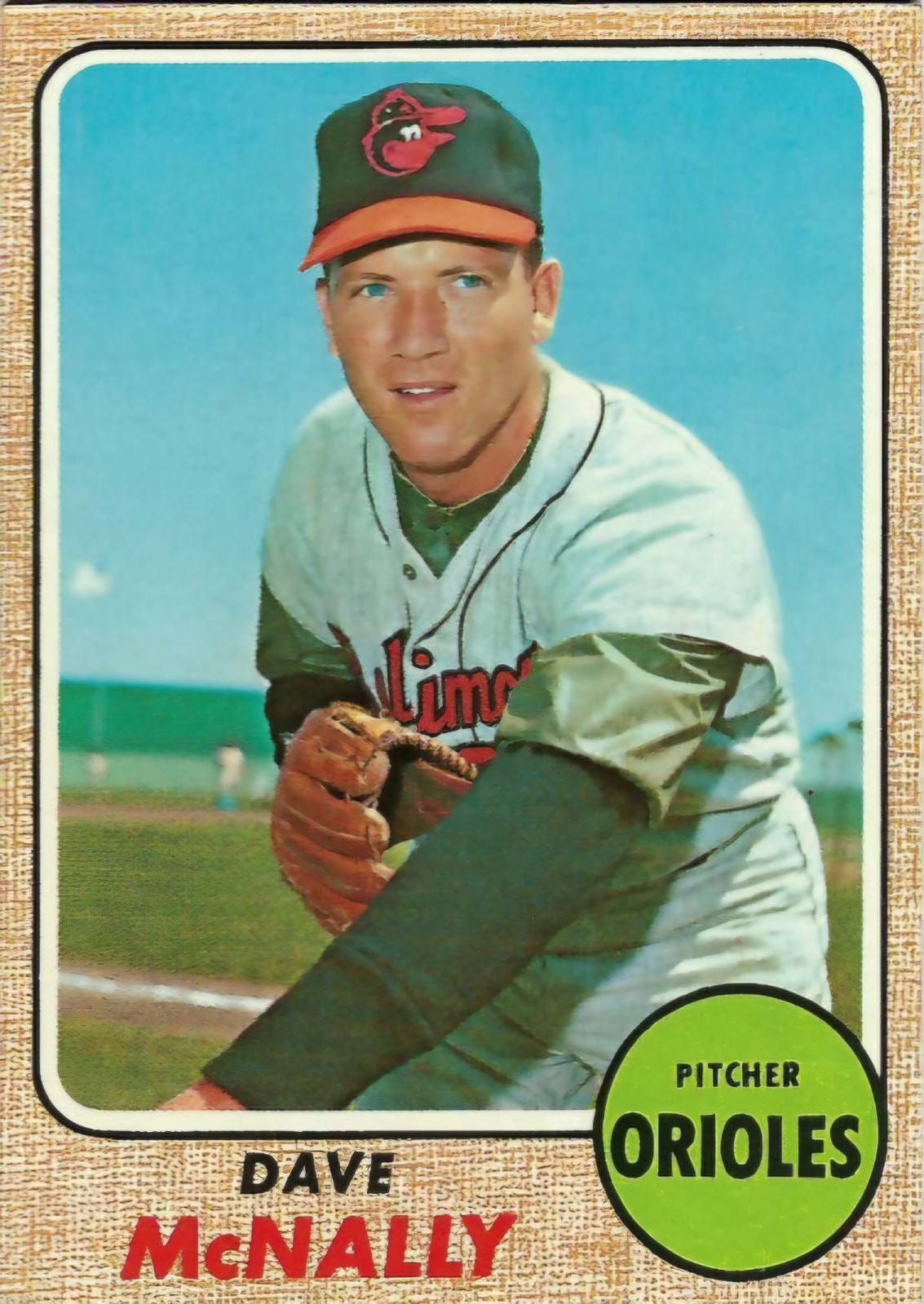

Many of his former teammates and superiors had good stories to tell about the left-handed pitcher from Billings, Montana.

It wasn’t because he was that staple of baseball storytelling, the zany clubhouse character. To the contrary, McNally was all business on and off the mound, although he did possess a wicked deadpan wit. He actually was the antithesis of zany, a devoted family man with a low golf handicap and plenty of business savvy, as evidenced by his success in the car business after baseball. (He moved back to Billings with his family and owned dealerships with his brother.)

No, McNally’s former teammates and superiors told stories about him for the best of reasons, because they admired him so.

He certainly gave them plenty of material with his play on the diamond. At age 23, McNally tossed a complete-game shutout against the Los Angeles Dodgers in Game 4 of the 1966 World Series, completing a sweep that brought a title to Baltimore. He allowed just three hits over 11 innings as the Orioles beat the Minnesota Twins, 1-0, in Game 2 of the 1969 American League Championship Series — possibly the finest performance of his career, he said later.

His favorite memory? The historic grand slam he hit against the Cincinnati Reds in Game 3 of the 1970 World Series. Never before had a pitcher cleared the bases with a home run in the Series. It hasn't happened since, and with the DH now in effect full-time in the Series, it almost surely will never happen again.

McNally won more games for the Orioles (181) than any pitcher not named Palmer, and he spread those wins among 13 seasons, becoming a fixture in the rotation during an era in which the Orioles were at or near the top of the game.

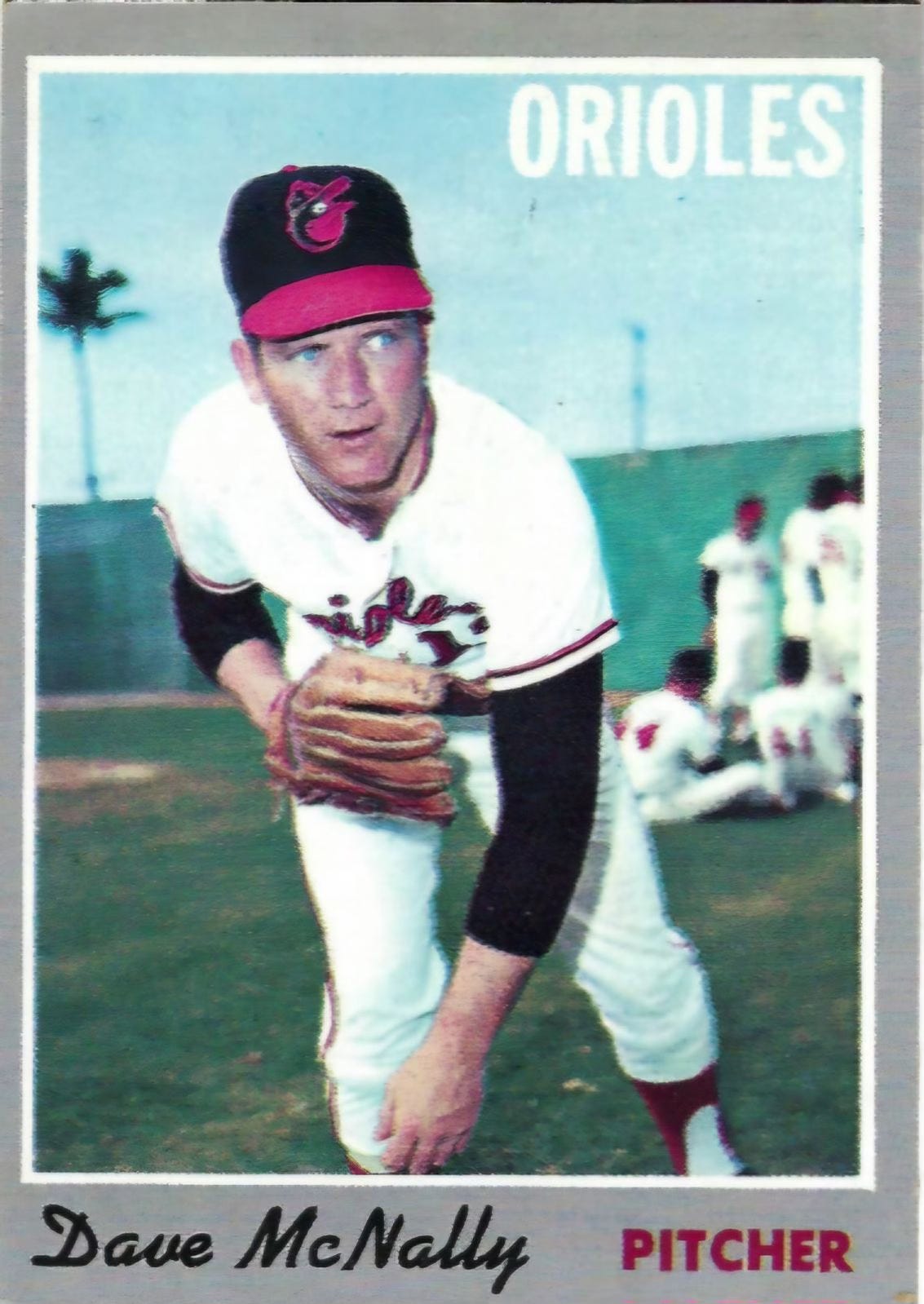

“He moved the ball in and out, and it was always right on the black (corners of the plate),” Boog Powell said in his Bird Tapes interview. “He worked quick. It was, ‘Let’s go, boys, let’s get it over with and get out of here; we’ve got better things to do.’ He didn’t have overpowering anything, but he was a magician with that stuff he had. He knew how to put a little bit on and take a little bit off and that was all it took.”

Frank Robinson said, “McNally was like a machine. No flair, no nothing, just got the ball and pitched. No matter what happened, whether you made four errors behind him, he’d say, ‘I got beat today, no problem.’ He didn’t say, ‘Well, if only they’d played a little better behind me,’ or anything like that. No excuses, ever. He got the ball and threw it, same every time. I didn’t like hitting against him in batting practice because he thew so nice and easy and then, boom, the ball was on you, jarring your hands. He wasn’t super fast, but he had that easy motion and the ball was on top of you.”

McNally excelled under pressure, as evidenced by his postseason ERA of 2.49 over 90 innings, which was more than a point lower than his regular season ERA. And he ended his career with a staggering total of 120 complete games, which isn’t that far from Sandy Koufax’s total (137) and underscores that McNally was determined to finish what he started, a valued trait before analytics overtook the game and it was decided that determination from your starter wasn’t as important when you could bring in a reliever throwing 100 mph.

“I learned tenaciousness from him,” Palmer, a Hall of Fame inductee, said in his Bird Tapes interview.

But the tenaciousness McNally possessed on the mound also exhibited itself in another realm - salary negotiations. And while his teammates certainly remembered him for his superb pitching, they really recalled his stubborn refusal to accept what the Orioles wanted to pay him.

Few other players across the major leagues, if any, were doing that in the late ‘60s and early ‘70s. In the years just before the players gained the right to free agency, teams still wielded all the power. The players’ union was just starting to disrupt norms. Salary arbitration wasn't in effect until after the 1973 season. Teams refused to deal with agents. A subpar season meant a player should expect a cut in pay the next year, and a good season meant, well, don’t expect too much. And if the player didn’t like it, too bad. His options were a) accept the offer or b) don’t play. With the reserve clause in effect, players were tethered to their teams until the team wanted a divorce.

A common thread in the Bird Tapes interviews with players from that era has been their frustrations with the game’s economic landscape when they were in uniform. The Orioles certainly gave them plenty to gripe about. Modest attendance at Memorial Stadium translated into modest revenues, which limited what the club wanted to pay.

“They had a budget and they were trying to live within that budget, and that’s just the way things were,” Brooks Robinson said. “No one knew what the other guys were making. That was better for the club and we never talked about it. McNally was the one who wouldn’t take it. He did it right. He was so stubborn. If he didn’t like the offer, he just said, ‘Well, I’m not signing, see you later.’ He fought them tooth and nail.”

The Orioles received an early look at McNally’s financial wiles when they were one of 10 teams pursuing him after his high school graduation in 1960. McNally’s mother brought in a CPA and one of Montana’s top criminal defense attorneys to help them navigate the situation. (McNally’s father had died in World War II). The Orioles and Dodgers wound up being the most interested, and the attorney pitted them against each other, driving up the price. McNally signed with the Orioles. receiving a bonus of $80,000. (Some reports have suggested the figure was higher.)

From that point forward, McNally sought to maximize what he earned. Once he became a fixture in Baltimore, he had a simple strategy. “I held out every year,” he told me in his interview for my book in 2000. (He died at age 60 in 2002.)

His holdouts took place at the start of spring training, after he’d received the Orioles’ offer for the season. (There were no multiyear contracts.) Without an agent, McNally negotiated directly with the Orioles’ GM, first Harry Dalton, and later, Frank Cashen.

“He was a team man all the way, a great competitor, a gentleman, a hell of a guy to have on the team. I will say this, though. When it came down to contract dealings, he was mercenary,” Earl Weaver said in his Bird Tapes interview. “He was as tough as any player I’ve ever seen. Every spring, Harry Dalton would start out with a dollar figure and McNally would just stay away from camp until Dalton got up to the figure Dave wanted. It was simple, really. Unless he got what he wanted, he wouldn’t play.”

After pitching the World Series clincher in 1966, he held out in 1967, hoping to earn more than the $18,000 he’d been paid the year before. He signed for a $7,000 raise.

“The first year I won 20 games (in 1969) I held out the next spring. I was bound and determined to get a $20,000 raise,” McNally said. “That kind of a raise was a horrendous thought to the ballclub. And then I got an agent. Brooks was the first, but I was among the first. They wouldn’t deal with him for awhile. Cashen just wouldn’t deal with him. The agent told me, ‘Don’t even talk to Cashen.’”

Cashen laughed about it years later in his 1999 interview for my book.

“McNally was a tough son of a bitch. Intractable was a good word for him,” Cashen said. “He was a special kind of an athlete. He was a guy who would go out and pitch, and if his fastball had nothing or his curve wasn’t working, he’d throw up more shit than you ever saw until he found something that was working. And he hung in there. He wouldn’t quit. If Earl went out to pull him, you’d think Dave was about to get in a fistfight with Earl. A lot of the stuff you saw across the negotiating table was the reason he was a great pitcher.”

McNally’s economic principle wound up making baseball history.

The Orioles traded him to the Montreal Expos after the 1974 season, but his arm had been hurting since the early ‘70s, and he abruptly retired at age 32 midway through the 1975 season. He’d never signed a contract with the Expos because he’d thought they were lowballing him, so he simply stopped pitching and went home.

Meanwhile, Marvin Miller, the head of the players’ union, was preparing to file a labor grievance challenging the reserve clause. To do so, he needed players who’d played a season without a contract, theoretically making them free agents at the end. The Dodgers’ Andy Messersmith had done it in 1975, but Miller needed more than one example. McNally agreed to add his name to the grievance even though he had no intention of ever playing again. The Expos tried to sway him, offering him a huge contract with a sizable guaranteed bonus just to come to spring training in 1976. It meant free money for McNally, but he turned it down and kept his name on the grievance, which the players’ union won later that year, effectively nullifying the reserve clause and giving the players the right to free agency.

It was too late for McNally to take advantage himself, but thanks to his principle, baseball players have made infinitely more money ever since.

Thanks for this writing John. He has always been my favorite O's pitcher. Love the Cashen quote about the fastball and curve not working and he would throw more crap until he found what worked. Tough ass competitor. Big game pitcher and a record in a WS game that will maybe never happen again.