The One Oriole Who Just Told Me No

When I published an oral history of the Orioles a quarter-century ago, I contacted over 100 current and former players and managers, executives, scouts and others. Only one refused to speak to me.

While accumulating as many interviews as possible with current and former players and managers, front office executives, scouts and others for my book on Orioles history a quarter-century ago, I found that each source belonged in one of four categories.

There were the sources I successfully tracked down, interviewed in person and recorded — the voices you’re now hearing as part of the Bird Tapes. I hope you feel, as I do, that they comprise pretty much an Orioles greatest hits album featuring Brooks Robinson, Frank Robinson, and dozens more.

Then there were the sources I successfully tracked down and interviewed, but only on the phone because, for one reason or another, I couldn’t get to them for an in-person interview. (Hey, I had a day job writing columns for the Baltimore Sun.) Unfortunately, those interviews went unrecorded.

Another category were the sources I wanted in the book but didn’t get to interview, mostly because they’d passed away or were too sick to participate. What a shame that Mike Cuellar, Jerry Hoffberger, Mark Belanger and Cal Ripken Sr., among many, weren’t able to expound on their roles in the franchise’s success.

Then there was the final category — the sources who didn’t make it into the book, even though I wanted them, simply because they didn't want to talk to me.

To be clear, these were the people whom I successfully tracked down, contacted and asked for time, only to be rebuffed.

Actually, it was a category of one, and I’m pretty sure you won’t correctly identify him even if I give you two dozen guesses.

No, it wasn’t Peter Angelos. The Baltimore attorney, who owned the team in a turbulent era and passed away earlier this year, was no fan of my newspaper’s coverage and steadfastly refused to talk whenever I asked him for a comment. So he’s certainly a good guess. But against all odds, he agreed to an interview for my book and gave me two hours. I recorded our conversation. It’s coming to the Bird Tapes later this summer. Yup.

Another good guess is Eddie Murray, the Hall of Fame first baseman who also was no fan of The Sun’s coverage and didn’t get along with many in the media, me included. I’m not sure we ever spoke one-on-one for The Sun, but again, against all odds, he consented to an interview for the book. And again, I recorded it, which means it’s coming to the Bird Tapes.

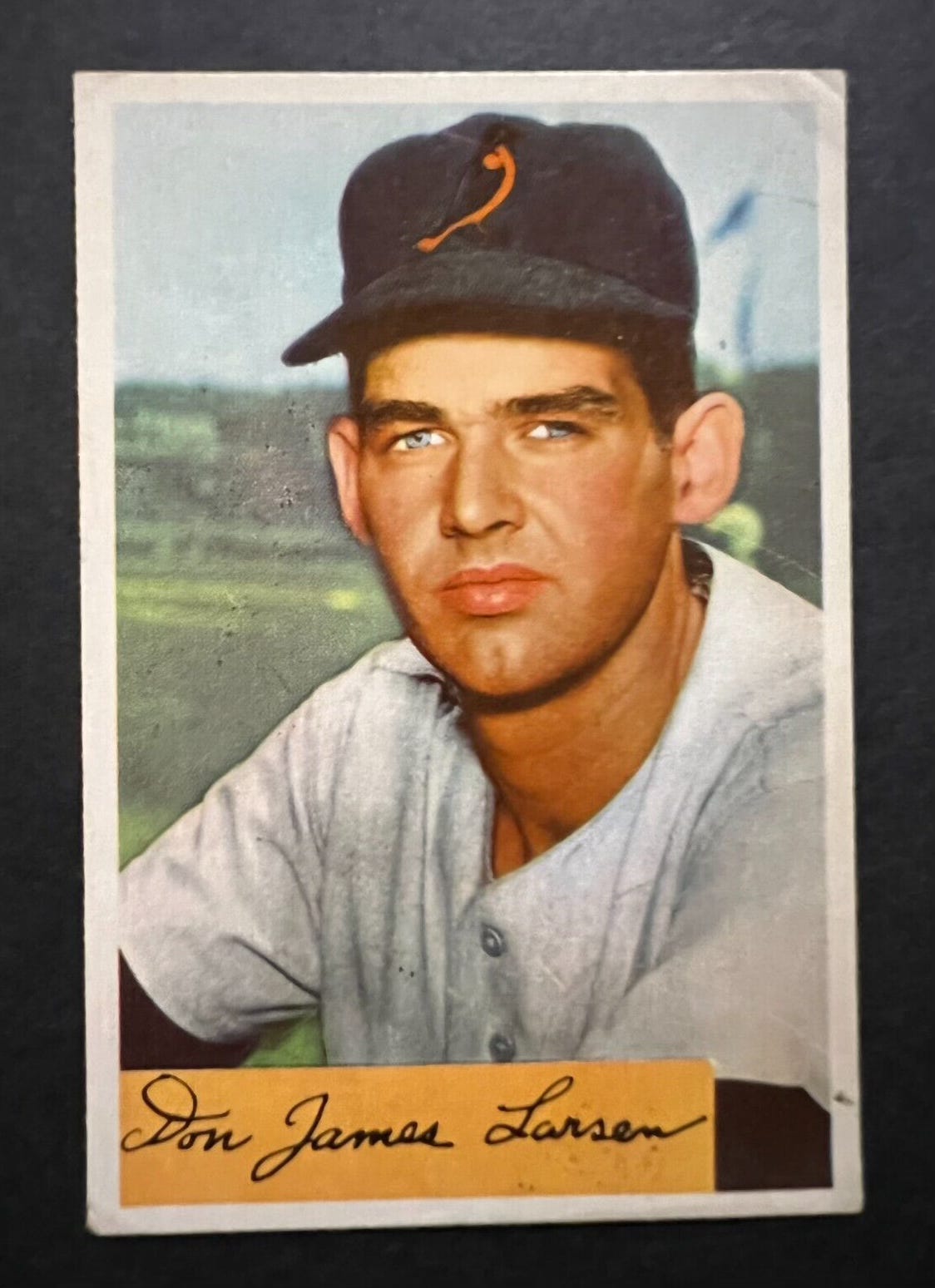

Give up? OK, the one person who flat-out turned me down was … drum roll … Don Larsen.

Yes, the same Don Larsen who gained baseball immortality in 1956 by throwing the only perfect game in World Series history.

Three years earlier, at age 23, he’d made his major league debut with the lowly St. Louis Browns and then moved to Baltimore with the rest of the team. Today, few fans recall that Larsen was one of the key members of Orioles manager Jimmy Dykes’ starting rotation in the team’s first season, in 1954.

Things did not go well. At all. Larsen posted a 3-21 record.

Seventy years later, the Orioles’ history includes numerous 20-game winners. But Larsen is still the only Orioles pitcher to lose 20 or more games in a season.

Soon after the 1954 season, he was traded to the New York Yankees as part of the 17-player deal Orioles manager/GM Paul Richards engineered, and he fared better in pinstripes, posting a 9-2 record in 1955. A year later, he retired all 27 batters he faced in Game 5 of the World Series against the Brooklyn Dodgers.

A tall right-handler with a buzz-cut hairstyle, he pitched in New York for three more years, winning 25 of 42 decisions, before being traded to the Kansas City A’s in the deal that brought Roger Maris to New York. He went on to pitch for several other teams, including the Orioles, in his final years in the majors, posting a 1-2 record with a 2.67 ERA in 27 appearances in his second act in Baltimore in 1965.

He was high on my list of former players I wanted to include in my book. He was a famous name and the story of his 21-loss season wasn’t well known. I’d seen him interviewed about his perfect game and he seemed chatty. I tracked him down in Idaho, where he as living, and called him. When he picked up, I introduced myself and explained what I was doing.

It’s a book on the history of the Orioles, I said.

There was a long pause.

“I’m going to say no,” he said.

No problem, I replied. I can call back another time.

“No, I mean I don’t want to do this,” he said.

“Why not? I won’t keep you long if that’s a problem,” I said.

“That’s not it. I just don’t want to do this. Sorry,” he said.

I tried to get him going with a couple of innocuous questions, an old trick, but he didn’t budge. I was going to have to write the book without him.

It was unfortunate, but if I was going to get a no, better that it was from someone who’d only played one year with the Orioles almost a half-century earlier, as opposed to one of the team’s signature names.

Still, it was disappointing.

I’ve always wondered why Larsen didn't want to talk to me, and I’ve developed a theory. Although his name is associated with perfection, he actually finished his career with a losing record in the majors (81-91). When he died at age 90 in 2020, his New York Times obituary noted that “his repertory of a fastball, slider and curve seemed weapons enough for a fine career” but “he had difficulty controlling not only his pitches but also his affinity for night life.” Later in life, he acknowledged that he underperformed, telling one interviewer, “I’m not happy with my career record. It could have been better. Partying had something to do with it. But I always needed companionship, even if there were just two people in town.”

My thought is his 3-21 season touched a nerve of regret he’d carried for decades, and he just didn’t want to rekindle those memories.

Duane Pillette, his teammate on the Browns and Orioles, told me in an interview for my book: “Larsen was just a big overgrown kid having a lot of fun. It wasn’t that he wasn't competitive. He just could have won a lot more. I roomed with him in St. Louis and I called him ‘Big Stupe,” which was the name of a cartoon character back then. The guy had a lot of talent, but he just didn't use it.”

Ernie Harwell, the Orioles’ play-by-play broadcaster in the 1950s, told me, “Larsen was a nice guy, but he liked to stay out all night. He was out all the time.”

I wish he’d wanted to talk about it all. A sportswriter lives on the willingness of athletes to muse on their shortcomings and what-ifs. You don’t just talk to winners.

But 3-21, that’s quite a stat. I guess I can see why Larsen said no.