The First Moment of Orioles Magic

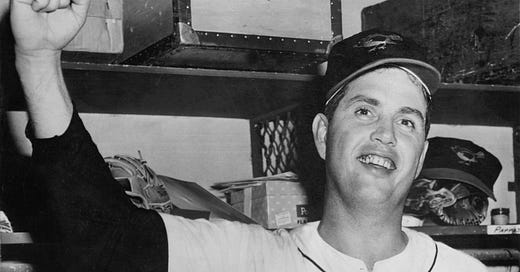

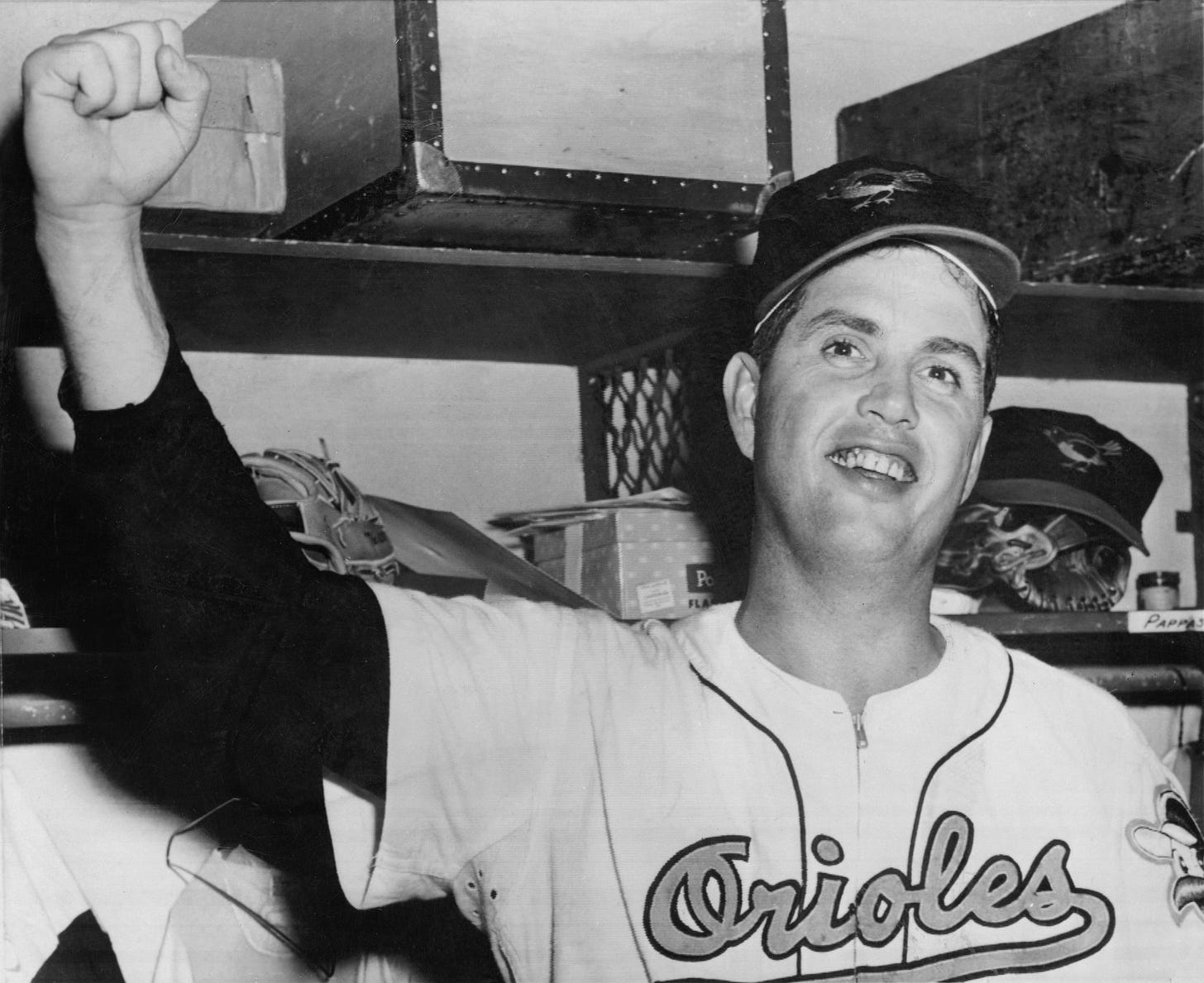

On a dreary afternoon at Memorial Stadium in 1958, knuckleballer Hoyt Wilhelm baffled the Yankees on national television.

It came out of nowhere on a day that appeared unlikely to provide memories, let alone history.

The Orioles were nearing the end of another losing season, their fourth in their first five years in Baltimore. They were playing the New York Yankees, who had already clinched the American League pennant.

Baltimore’s starting pitcher was a 35-year-old making just his third start for the team after having recently been claimed off waivers. His name was Hoyt Wilhelm. More than a few baseball insiders believed his career was nearly over.

The setting was dismal. Dark gray clouds hovered over Memorial Stadium on a Saturday afternoon. Rain began to spit in the early innings, and then a harder drizzle settled in. Many of the 10,941 fans sought cover.

But the teams kept playing, and on September 20, 1958, the first indelible episode of Orioles Magic unfolded.

Wilhelm had fashioned a solid major league career with a trick pitch, the knuckleball. His danced and dipped unpredictably as it traveled to the plate. “Best knuckler I ever saw. When he threw it overhand, it broke straight down, When he threw from the side, it broke to the side,” said Harry Brecheen, a longtime pitching coach for the Orioles, in an interview for my book on the team’s history a quarter-century ago.

Dick Williams, who played for the Orioles in their early years and later became a World Series-winning manager, told me, “They talk about Phil Niekro’s and a few others, but Hoyt’s knuckleball was the best. He threw it harder. He claimed he knew which way it was going to break, but I don’t know how he did.”

Born in 1922, Wilhelm had developed a knuckler as a North Carolina high schooler because he didn’t like his fastball velocity. He tossed his first professional pitch in the low minors before World War II, and after earning two Bronze Stars and a Purple Heart during the war, finally made it to the majors at age 29 in 1952. He thrived for several years as a relief pitcher with the New York Giants, coming on late in games and baffling hitters accustomed to fastballs.

But his effectiveness waned and he’d been traded once and waived twice by the time he faced the Yankees on that rainy Saturday afternoon in 1958.

Paul Richards, the Orioles’ manager and GM in the 1950s, had a knack for helping veteran pitchers become more effective and extend their careers. Richards had claimed Wilhelm with the idea of turning him into a starter.

With a pennant in hand and a World Series ahead, Casey Stengel, the Yankees’ manager, rested catcher Yogi Berra and several other starters. But his lineup still featured Mickey Mantle and numerous mainstays.

Wilhelm’s knuckler was baffling from the outset. He retired the Yankees’ first seven hitters before walking Bobby Richardson with one out in the third. Richardson was caught stealing by Orioles catcher Gus Triandos and a flyout ending the inning.

As the rain increased, three Yankees tried to bunt their way on base, frustrated by the knuckler and hoping the wet grass would challenge fielders to make plays. But Wilhelm threw two out and Triandos retired the other.

The conditions eventually grew so dank that the umpires asked that the stadium lights be turned on. It didn't help the hitters. The Yankees’ starter, Don Larsen, matched Wilhelm out for out, allowing just one hit, a bunt single, through six innings.

Larsen was more familiar to Baltimore fans than Wilhelm, having lost 21 games as a starter for the Orioles in 1954 before tossing a perfect game for the Yankees in the 1956 World Series. But he was on the other side now. The fans braving the rain got behind Wilhelm, who dealt with just three baserunners in the first six innings — two who’d reached via walks, the other by error.

After Wilhelm retired the Yankees in order in the top of the seventh to keep the game scoreless, Stengel pulled Larsen for Bobby Shantz, a left-hander who’d won 24 games with the Philadelphia Athletics in 1952. Shantz was still effective in a combination starter/reliever role, but Triandos, the first batter he faced, mashed a pitch 410 feet over the center field fence, putting the Orioles ahead, 1-0.

After the game, Wilhelm said he didn’t think about throwing a no-hitter until Trinados gave the Orioles the lead. “You’ve got to have a run. Until then, I was just thinking about the winning a game,” he said.

A young defensive replacement named Brooks Robinson entered the game, playing third base, in the top of the eighth, and Wilhelm’s no-hit bid almost ended when the Yankees’ Norm Siebern hit a sharp grounder in the hole between first and second. Billy Gardner, the Orioles’ second baseman, ranged far to his left, fielded the ball and threw to first for a bang-bang out. One out later, Berra strode to the plate as a very dangerous pinch hitter but grounded out.

In the top of the ninth, with the small crowd on its feet in the rain, Richardson flew out to center for the first out. Enos Slaughter, pinch-hitting for the pitcher, hit a line drive to right, but the Orioles’ Willie Tasby chased it down for the second out.

That brought outfielder Hank Bauer to the plate as the Yankees’ last hope. Eight years later, he would help bring a World Series title to Baltimore as the Orioles’ manager. But on this day in 1958, he sought to spoil Baltimore’s fun, squaring around and bunting the first pitch from Wilhelm. The ball rolled foul as the crowd booed.

Two pitches later. Bauer popped out to Gardner, and Wilhelm, his no-hitter complete, was mobbed by his teammates.

The Orioles had hosted an All-Star Game earlier that summer, but Wilhelm’s gem was the first achievement by one of their players that wowed fans across the country. Weeks later, the Yankees would win their seventh World Series title in the past decade. A no-hitter against them was a feat. And while only a sparse crowd saw it in person, millions saw it on national television via a Game of the Week broadcast.

First pitch to last, the game lasted one hour and 48 minutes.

It hinted at what lay just ahead in Baltimore. Before the no-hitter, the Orioles were 111 games under .500, a nonentity in the American League, since arriving in Baltimore in 1954. Soon after the gem, they’d go on a run that included just two losing seasons between 1960 and 1985.

Wilhelm would continue to pitch well for them, winning 15 games with a league-low 2.19 ERA as a starter in 1959. He added 11 wins in 1960 as he transitioned back to a relief role. The Orioles traded him to the Chicago White Sox in the deal that brought shortstop Luis Aparicio to Baltimore in 1963.

His baseball fortunes had appeared increasingly dim when he first joined the Orioles, but his no-hitter altered his career trajectory. He wound up pitching in the majors until he was 49 years old in 1972 and retired as the all-time leader in appearances (1,070), having broken Cy Young’s record.

Safe to say, your bona fides as a historical figure are assured when you’re breaking Cy Young’s records. Wilhelm then effectively opened the doors of the Hall of Fame to relief pitchers when he was inducted in 1985.

I didn’t interview Wilhelm for my book on the history of the Orioles, and for the life of me, I can’t remember why I didn't get him. He was still alive, living in Sarasota, Florida. He only pitched in Baltimore for a few of his many years in the game, but he was a true icon of twentieth-century baseball and he gave the Orioles their first moment of sheer triumph.

(Note: if you’re a free subscriber to the Bird Tapes, please consider upgrading to a paid subscription. You’ll hear my vintage interviews with Orioles players and gain unlimited access to the archive of those interviews as it grows. Free subscribers receive written posts such as this one but can’t access the interviews.)

.

I thoroughly enjoyed your story, probably more than most, because I was there that day with my dad. I was only six years old and it may or may not have been my first game, but it's definitely the first game I remember. We lived in Catonsville and, since my dad didn't have a car, we took the #8 streetcar all the way to Greenmount and 33rd St (almost an hour trip)and walked from there. My dad's favorite seats were general admission on the third base side in left field under cover of the upper deck grandstand. As the years went by, it was nearly always our spot to see a game. But this particular game I always remembered. The weather was lousy, but we were dry. In those days, they sold popcorn in a cardboard container in a shape of a cheerleaders megaphone. Once I ate the popcorn I could use it to cheer and when Gus hit that homer, I was screaming into it. Needless to say, Gus & Hoyt were my first Orioles heroes. And as fate would have it, the next year Hoyt rented a house in my neighborhood and I got to meet him many times. Thanks, John!

Very well done, a pleasure to read. You still got it, John!