The Birth of Baseball's Data Revolution

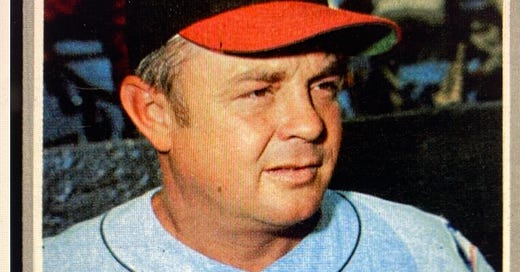

Among the many subjects he discussed In his Bird Tapes interview, Earl Weaver told an important origin story.

Trying to pad a slim lead late in Wednesday’s win over the Los Angeles Angels, Orioles manager Brandon Hyde asked catcher James McCann to try to lay down a sacrifice bunt. McCann’s first two bunt attempts failed, seemingly ending his chance to advance the two runners on base. But Hyde asked him to try again.

Attempting a bunt with a two-strike count is an unconventional play, rarely seen, largely because a fouled attempt produces strike three, unlike a foul on a regular swing. The odds of a strikeout are significantly raised, and sure enough, McCann fouled off the pitch for strike three.

My initial reaction was to yell at Hyde through the television. Why had he basically wasted an out in a close game?

But I seriously doubt Hyde was managing strictly with his gut when he asked McCann to bunt with two strikes. These days, managing strictly with your gut is about as common as the windmill windup that pitchers used in the 1950s.

To be clear, I don’t know for a fact what drove Hyde’s decision-making, but given baseball’s intensely data-driven nature in 2024, he almost surely possessed some kernel of information indicating that, say, his team had a higher win-probability percentage if McCann attempted a two-strike bunt with the Orioles ahead and trying to plate two base runners with no outs in the top of eighth.

Or, you know, something like that.

Such numbers and the algorithms that produce them are now as commonplace in baseball as balls and bats and impact a lot of important decision-making. The game is radically different from the game Earl Weaver encountered when he became the Orioles’ manager in the late 1960s. Incredible as it sounds now, barebones statistics were the only data in widespread circulation in those days. Batting averages and home run totals. Won-loss records for pitchers. Errors. Runs batted in.

No one knew how hard a pitcher threw or precisely how far a ball was hit. Launch angle? Was that a NASA thing? A win-probability algorithm? Any manager who admitted factoring that into his decision-making wouldn’t hold a job for long. Sounds awfully nerdy.

When the Orioles fired Hank Bauer and replaced him with Weaver in the middle of the 1968 season, it was truly impossible to envision the evolution and easy availability of complex and comprehensive data and how much it would overtake baseball.

But every revolution has a first shot.

When Weaver took over, the Orioles were six games over .500. By the end of the 1968 season, they were 20 games over .500. Although they finished a distant second behind the Detroit Tigers, they were on the right track. And after managing for a half-season in the majors, Weaver was onto something.

As he recounted in his Bird Tapes interview, posted earlier this week, he went to Bob Brown, the Orioles’ director of public relations, and asked a question.

“How hard would it be for you go back a year and tell me how Boog (Powell) is hitting against (Detroit’s Mickey) Lolich? And what every player on the team is hitting against him?” Weaver called. “Bob said, ‘That wouldn’t be hard at all.’”

The next year, before every series, Brown presented Weaver with several sheets of paper reflecting how the Orioles hitters had fared historically against the opposing team’s pitchers. These weren’t computer printouts. Brown wrote it all out longhand.

“Boog, for instance, was 1 for 25 against Lolich,” Weaver said.

Thus, Powell, the Orioles’ signature slugger, was on the bench when the Orioles faced Lolich. Weaver altered his lineup to fit the situation, a departure from the norm in a simpler era when many managers mostly just relied on their best players, regardless of specific situations, and rolled out the same lineup in game after game.

Ahead of what would became an enormous, all-encompassing curve of change, Weaver took data, unknown to others, and used it to tinker. The impact was colossal. The Orioles won 109 games and the American League pennant in 1968, 108 games and a World Series title in 1970 and another American League pennant in 1971.

Sure, it helped that they had a lineup and a pitching rotation loaded with All-Stars and future Hall of Famers. But Weaver’s forward-thinking machinations contributed to making it all hum.

Weaver and I didn’t discuss all of his advanced analytical ideas during our interview in the fall of 1999. He famously carried around, and consulted, index cards reflecting tendencies and individual scouting reports. In 1972, he had the idea to use a radar gun to track a pitcher’s velocity.

Mark Belanger, a career .228 hitter, could hit Nolan Ryan, so he played when other, better hitters on the Orioles didn't because they struggled against Ryan.

Weaver’s use of individual hitter-pitcher results peaked in 1979 when Gary Roenicke and John Lowenstein shared left field and combined for 36 home runs and 98 RBIs on another pennant-winning team.

It is interesting to muse on how Weaver would have managed, what data he would have used, if he were managing today with its volume of information about spin rates and off-the-bat power and GPS-backed tendencies so readily available.

My first hunch: He would have loved the infield shift.

But my point is it essentially all started, for everyone, with his single, simple question to Bob Brown before the 1969 season.

Baseball was never the same again.

The job as a Sports reporter and anchor at WJZ-TV in Baltimore. I sat down near Earl in the dugout before an Orioles night game. After introducing myself, I asked the manager which Orioles hitters had trouble hitting that night’s starting pitcher. Without looking at me he reached for his right hip pocket and pulled out those famous hitter/pitcher matchup numbers. And gave me his insight on four of his hitters who COULD hit the upcoming starter. It was priceless! Even more so when another reporter was headed our way and Earl slipped the cards back into his pocket. Just one of my well remembered Weaver stories. Andrea Kirby

I once witnessed—and benefitted from—Earl Weaver’s analytics. It was my first week on