The Bird Tapes Interview: Peter Angelos (Part 2)

In the second part of his vintage interview, the late owner vehemently denies he's a meddling owner, yet takes the blame for the doomed signing of Albert Belle.

Peter Angelos was celebrated throughout Birdland in 1993 when he bought the Orioles in a New York bankruptcy court.

Since the late 1970s, the team had been owned by Edward Bennett Williams, a lawyer from Washington DC, and Eli Jacobs, an investor based in New York. For much of that time, the team’s future in Baltimore was considered dubious, especially after football’s Colts, owned by Robert Irsay, a Chicago businessman, left for Indianapolis in 1984. Fans feared the Orioles might follow the Colts out of town because their ownership also wasn’t tied to the city.

As it turned out, those concerns eased before Angelos bought the team; the Orioles had moved into Camden Yards in 1992 and signed a 30-year lease. They weren’t going anywhere. Still, Angelos was cheered for putting them back in the hands of local ownership. All was right again in Baltimore’s baseball world, it seemed.

Angelos’ honeymoon with Baltimore fans continued into 1994, when the Orioles fielded a winning team while playing before packed houses at Camden Yards until a labor dispute halted the season and ultimately cancelled the World Series.

Slowly, though, a concerning aspect of Angelos’ ownership style began to surface, at least in the fans’ eyes. Angelos had opinions about baseball matters, it seemed, and he was inserting himself into the Orioles’ decision-making in that area.

Having a non-expert involved in baseball decisions was and is a dangerous road for any team to go down. In the second and final part of my vintage interview with Angelos, recorded in 2000 and available below to paid Bird Tapes subscribers, he vehemently denies the charge.

“The impression of meddling is false,” he thunders. “There isn’t one player on this team that I’ve picked.”

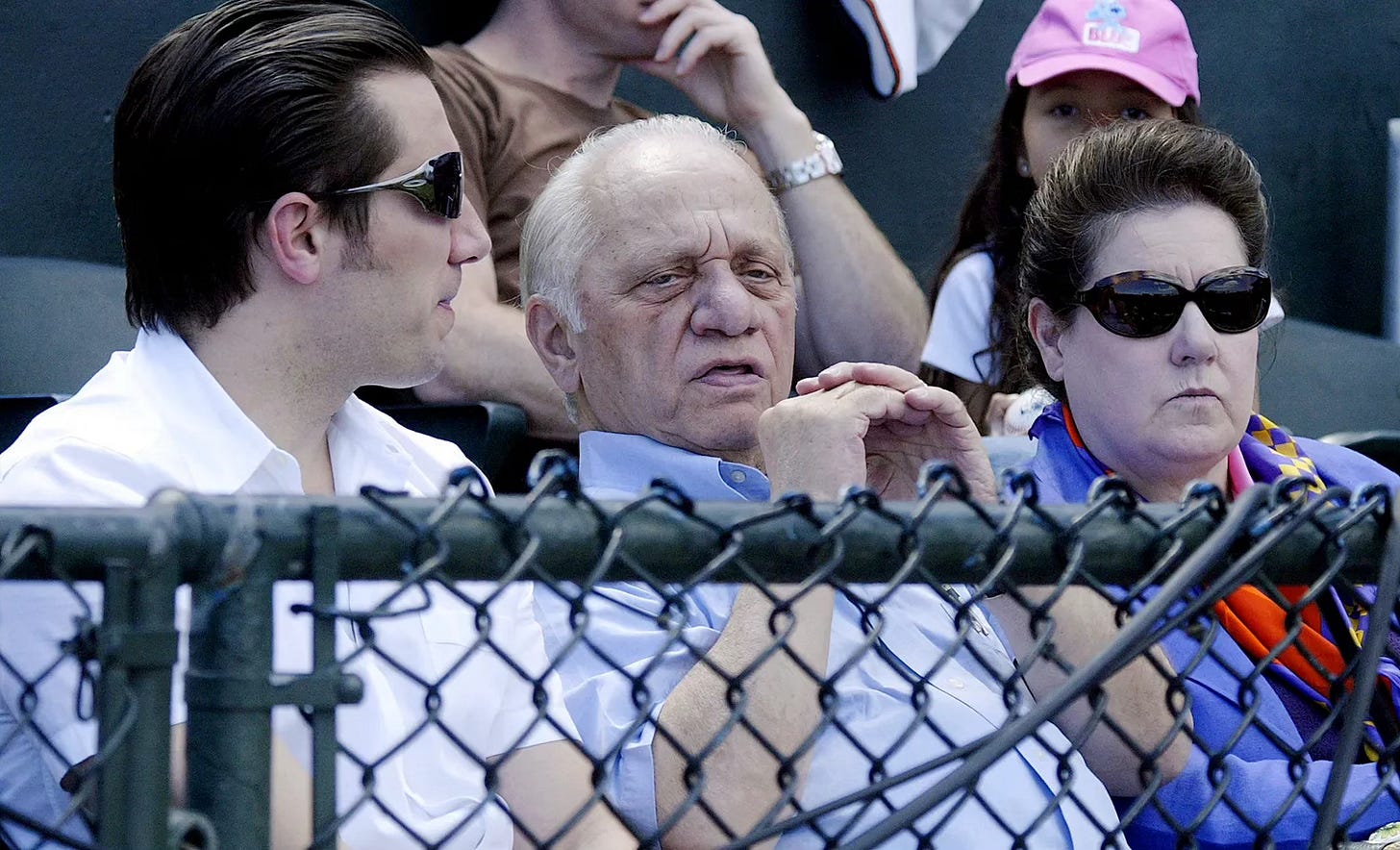

Despite his protestations, Angelos would continue to face the charge of meddling throughout his long run as the Orioles’ owner, which ended when his family sold the team to David Rubenstein earlier this year. Angelos died in June at age 94.

In our interview, he blames his image as a meddler on reporters, especially those at the Baltimore Sun, where I worked from 1984 through 2007. The newspaper isn’t accurately reporting his involvement in many situations, Angelos says.

A few minutes after he denies being a meddler, though, he admits he pushed hard for the front office to sign Albert Belle, the All-Star slugger who tore up the American League for the Cleveland Indians (now Guardians) and Chicago White Sox before the Orioles made him the highest-paid player in baseball at age 32, signing him to a five-year, $65 million deal in late 1998. But his power numbers dropped in Baltimore. When I interviewed Angelos, Belle was nearing the end of a season with his lowest RBI output in nearly a decade.

Not along after we spoke, the situation bottomed out and Belle had to retire due to a hip condition, leaving the Orioles on the hook for millions.

“I had a lot to do with that (decision to sign Belle),” Angelos says. “(Orioles GM Frank) Wren said it was a ‘no-brainer’ and I was all for it. I‘ll take my full share of the blame and maybe more than I would assess to Frank.”

Overall, though, he insists he lets his “baseball people” make baseball decisions, using the failed signing of relief pitcher Mike Timlin as an example. Timlin had pitched relatively well for nine years in the majors, but only intermittently as a closer, when the Orioles signed him to be their closer in 1999.

“When Frank told me he’d signed Timlin to a four-year deal, I said, ‘You did what?’” Angelos says.

Timlin lost his job as the closer amid a flurry of blown slaves and was traded less than two years into the deal.

“Timlin has demoralized the team for two years (with blown saves),” Angelos says. “We’re going to get a closer.”

In Part 1 of the interview, posted last week, Angelos admitted he’d suggested to then-manager Johnny Oates in 1994 that a young player named Leo Gomez should play third base — a suggestion Oates didn’t act on, at least not permanently. That conflict made it onto the sports pages and was one of the first indications that Angelos was going to be more involved on the baseball side than Jacobs, the prior owner. (Edward Bennett Williams also had dictated some baseball moves in the 1980s, as Hank Peters, the GM at the time, detailed in his Bird Tapes interview.)

In Part 2, Angelos reveals that he strongly suggested to Wren that the team keep relief pitchers Armando Benitez and Alan Mills, both of whom left via free agency, weakening the bullpen.

In short, Angelos is neither lacking for opinions nor afraid to voice them, yet he steadfastly denies he is involved in the baseball operation any more than an owner should be when millions of dollars are on the table.

“Owners should be and ARE consulted for big decisions,” he said in Part 1.

In Part 2, he alternates between defiance and humility on the subject.

“I’ve taken on bigger adversaries than The Baltimore Sun,” he says, reaffirming that he believes the newspaper is the problem, and that he’ll continue to fight to get his side of various stories told properly.

But then he says, “Some people will say I should have performed better as the head of the club, conceding that he had “made mistakes.”

As with Part 1 last week, Part 2 offers another rare glimpse at the fascinating, complex man who owned the Orioles far longer than anyone in their history.

Keep reading with a 7-day free trial

Subscribe to The Bird Tapes to keep reading this post and get 7 days of free access to the full post archives.