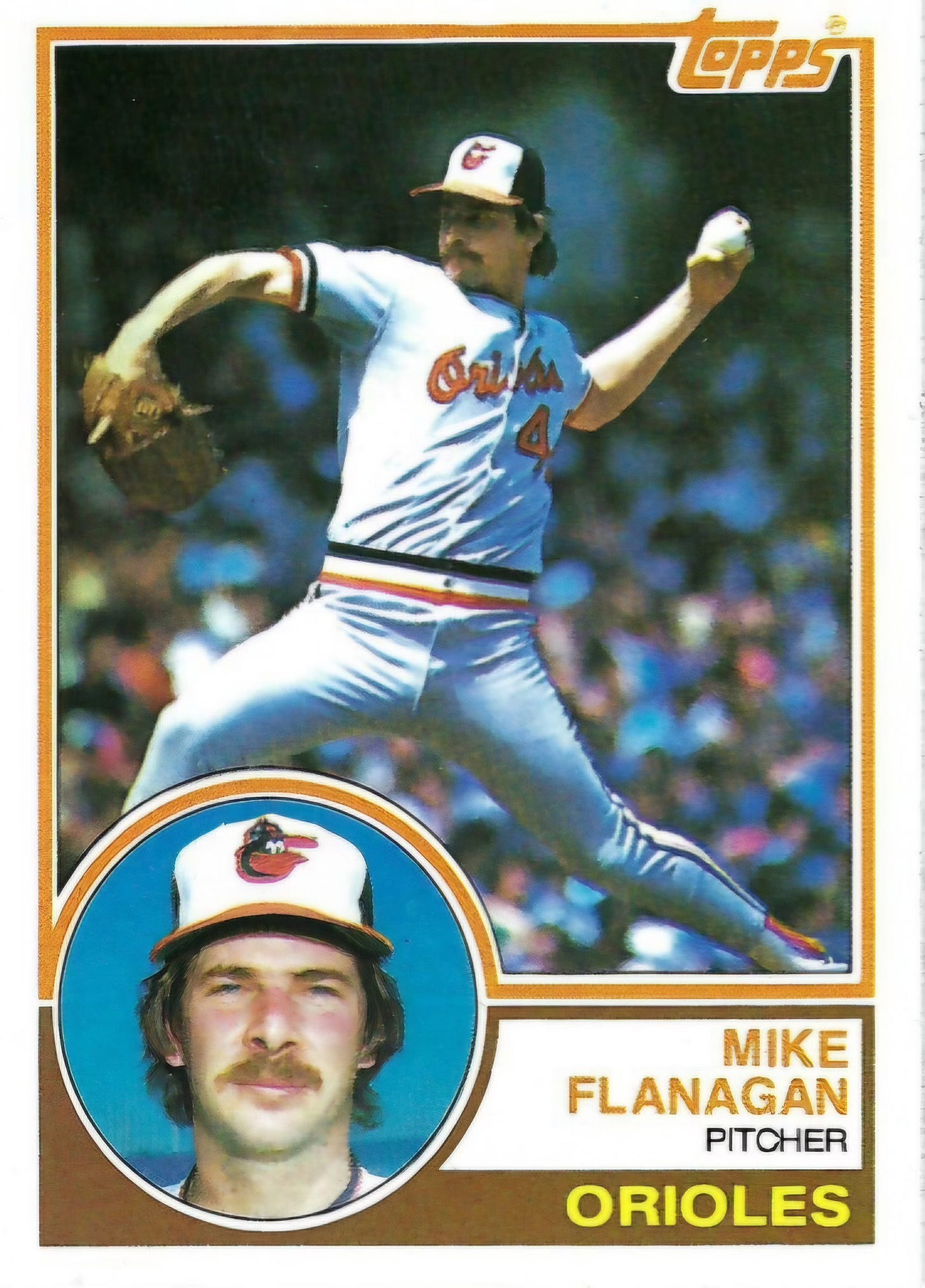

The Bird Tapes Interview: Mike Flanagan

In his vintage interview, he poignantly evokes the blend of personalities, fundamentals and camaraderie that made the Orioles so special from the mid-1970s through their World Series victory in 1983.

I wrestled with how to handle my vintage interview with Mike Flanagan, whose death at age 59 in 2011 rattled Birdland like few events in Orioles history. I feared that hearing him might upset some people or somehow seem inappropriate.

But once I listened to our conversation from a quarter-century ago, I felt my path forward on the matter was clear.

When we spoke about his career and his era of Orioles history in the clubhouse at Camden Yards in 1999, the qualities that made him so beloved were fully evident. He was expansive and witty, a superb historian. Among the nearly 100 interviews I conducted for From 33rd Street to Camden Yards, my book on Orioles history published in 2001, none was better at distilling what made the Orioles so special for so long.

The interview presents Flanagan at his very best and I believe it belongs in the Bird Tapes collection alongside my interviews with the franchise’s other greats.

Honestly, the collection would be incomplete without it.

After joining the organization as a seventh-round draft pick in 1973, he learned the tenets of the Oriole Way at the lowest levels of the minor leagues, believed those tenets, preached them, understood them and was proud beyond measure of the winning force they generated on the diamond.

Throw strikes.

Catch the ball.

The importance of a single out.

Play smart.

Let the other guys lose the game.

Decades later, it’s funny to hear others boil down the Orioles of his vintage (late 1970s and early 1980s) to the three-run homers manager Earl Weaver liked so much. Those were important, but the Orioles won year after year in that era because they were smart, sound, pitched well, played together, knew each other, liked each other, bonded over dealing with Weaver’s furies (“the time bomb in the dugout,” Flanagan called him) but also understood that Weaver made it all work.

They won a World Series after Weaver left and just before the machinations of free agency changed the nature of the game, making it impossible for a core to remain together for as long as theirs did.

Everyone plays a role in such a collective, on and off the field. Flanagan was the poet as well as a pitcher. Listen to him explain how the heart of their collective was the rollicking camaraderie found on the bus taking them to and from games on the road. There was just one bus, with everyone crammed on. Weaver sat in front, like a general leading his troops. The guys in the back, by the toilet, doled out insults and praise.

They rode together day after day, year after year, culminating with their trip from Philadelphia back to Baltimore after they won the World Series in 1983.

It couldn’t last forever and it didn’t. Players from other organizations filtered in, including what Flanagan called “some non-believers.” Flanagan himself left, traded to Toronto. Ralph Salvon, the team’s loyal and beloved trainer, passed away. When Flanagan rejoined the Orioles in 1991 for a second act as a relief pitcher, there was no longer a single bus. The coaches and manager traveled separately from the players to and from games.

It spoke volumes. The era was over.

In our interview in 1999, Flanagan barely discussed the Cy Young Award he won in 1979. But he talked on and on about the bus.

Although other players with more luminous records have worn the Orioles’ uniform, it was fitting that Flanagan was called upon to throw the last pitch at Memorial Stadium in 1991 before the team moved to Camden Yards. No one who’d worn the uniform was better at articulating why the ballpark and its era of baseball evoked such powerful memories for so many.

He was a delight as a player, coach, broadcaster and executive over nearly four decades with the organization. A year after he took his life, his wife told Dan Rodricks, my former colleague at The Baltimore Sun, that he had battled depression for years. (Rodricks and Flanagan were fishing buddies.) It complicates remembrances of him, but my aim in posting our vintage interview is, simply, to honor the star he was and his singular contribution to the chronicle of Baltimore baseball history.

Keep reading with a 7-day free trial

Subscribe to The Bird Tapes to keep reading this post and get 7 days of free access to the full post archives.