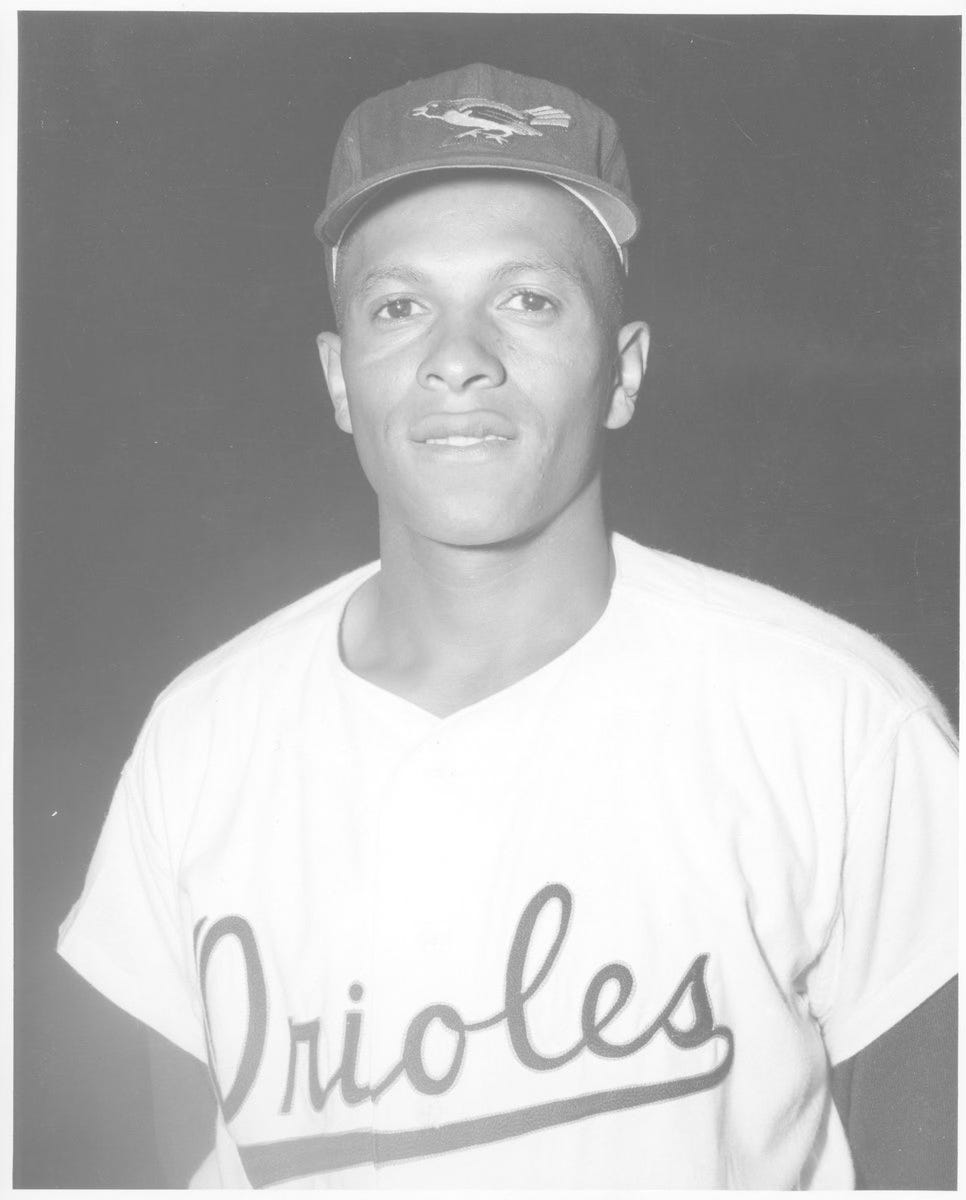

The Bird Tapes Interview: Joe Durham

In 1954, he became the first Black player to hit a home run for the Orioles. In an interview years later, he spoke more about why his career never launched like the ball he hit that day.

The Orioles had a 1-0 lead over the Philadelphia A’s on September 12, 1954, before 12,981 fans at Memorial Stadium when a Baltimore outfielder named Joe Durham strode to the plate to lead off the bottom of the sixth inning. A 22-year-old late-season call-up, Durham was batting over .300 since being promoted, exhibiting enough potential that Orioles manager Jimmy Dykes was batting him third in the order.

The first pitch from Philadelphia’s Al Sima was a ball. The second pitch was a hanging slider, and Durham, tall and lithe, swung hard and crushed it. The ball flew over the infield, over the outfield and over the left-field wall. Durham circled the bases as the scoreboard showed that the Orioles now led, 2-0.

His home run was mostly forgotten when the A’s rallied to win the game, dropping the Orioles’ record to 48-96 in their first season in Baltimore. But Durham had made history. The 16 other players who’d already hit home runs for the Orioles that season shared one characteristic: they all were white. Durham, with that clout, became the first Black player to hit a home run for the Orioles.

The organization eventually produced a long line of Black stars that included Paul Blair, Frank Robinson, Al Bumbry, Eddie Murray and Adam Jones, among many. Durham was where it all started. With his promotion in 1954, he became the club’s first Black position player. And then he hit that home run.

But more than 40 years later, when I interviewed him for my book on Orioles history, he barely discussed his role as a racial pioneer. Durham was far more interested in explaining why, in his view, his Orioles career never launched the way his home run did that day at Memorial Stadium. He pointed an accusing finger at Paul Richards, who was in charge of the Orioles as both their manager and GM in the 1950s.

“That man was the most critical, racial SOB I’ve ever seen in my life,:” Durham told me.

The criticism Durham offered throughout his scathing interview, which is available below to paid Bird Tapes subscribers, certainly provided an alternate view of Richards, who was widely hailed in other interviews for my book as an innovative baseball savant who helped build the Orioles into contenders. Durham contended that Richards did so with veiled prejudice against Black players.

“Playing for him was worse than playing in the Texas League,” Durham said, referencing a minor league in which Black players routinely experienced racism and segregated living conditions in the 1950s.

Richards was the Chicago White Sox’s manager when Durham debuted with the Orioles late in the 1954 season after posting solid numbers in the minors for several years. Durham then missed the next two seasons while fulfilling a military service commitment, and while he was gone, Richards joined the Orioles and began to maneuver with unchecked authority. When Durham completed his military service and resumed his career with the Orioles in 1957, “God was managing,” Durham told me dryly.

Now 25, Durham led the Orioles with a .296 batting average in spring training in 1957, drawing a compliment from Richards. “That boy could develop into a major league star,” the manager said, according to a Society of American Baseball Research profile of Durham, A white supervisor using the word “boy”to describe a Black adult male was and still is considered racist.

Despite his strong spring performance, Durham started the year in the minors, at Double A, where he hit .391 before being called up to Baltimore in early June after one of the team’s outfielders went out with an injury. Durham started 17 straight games upon arriving, but he struggled, as do many players when they’re receiving extended playing time in the majors for the first time. Durham’s opportunity dwindled.

Richards believed Durham was lunging at pitches, cutting down on his balance when making contact. Seeking to fix the issue, Richards tried an experiment in the batting cage after a Sunday afternoon game in which Durham had gone hitless. A rope was tied around Durham, and when a pitch came toward him, an Orioles coach pulled on the rope to keep him from lunging as he swung.

Durham was appalled at the time and even more furious years later as he recalled the horrifying optics of a white coach tying a rope around a Black player.

“That was one of his brilliant ideas. I tell you, he was a genius,” Durham said disgustedly about Richards. “But you couldn’t say anything back then.”

Richards never tied him up in the cage again. But Durham never played more than two games in a row after that even though he was with the Orioles for the rest of the season. The St. Louis Cardinals took him in the Rule 5 draft in 1958 but returned him to the Orioles, and after that, Durham spent the rest of his career (six years) in the high minors, playing alongside Brooks Robinson, Boog Powell and others as they passed through on their way to stardom in Baltimore.

“I died in Triple A,” said Durham, whose career, in the end, consisted of 4,456 plate appearances in the minors and 256 in the majors.

It was not unusual for Black players to face heightened scrutiny from the decision-makers who controlled rosters in the ‘50s and early ‘60s. Although the major leagues finally were integrated, only a trickle of Black players received chances at first. That was especially true in the American League, which lagged far behind the National League in opening up wholeheartedly to integration.

“It was hard (for a Black player) to play in those years,” Durham said. “Then you run into a guy like Richards.”

Richards, who managed the Orioles from 1955 through 1961, did give several Black players chances. He traded for Connie Johnson, a pitcher who made 72 starts for the Orioles from 1956 through 1958 and led the team with 14 wins in 1957. Bob “The Rope” Boyd hit .301 as the Orioles’ regular first baseman from 1957 through 1959.

But Johnson, in his interview for my book, told me, “I don’t think Richards liked Blacks too much. He’d hide it in ways you wouldn’t notice if you didn’t come looking for it. But I noticed.” And Boyd, according to Durham, “was very scared of Paul.”

When the Orioles began the 1962 season with an all-white team, Civil Rights groups considered picketing Memorial Stadium. A reporter asked Richards, now in Houston as the GM, if the team he’d left behind served as an indication that he might be prejudiced. “If you want to think that, OK,” Richards replied, “but go ask Connie Johnson and Bob Boyd if they think I’m prejudiced.”

Durham left no doubt about how he’d answer that question. A career .272 hitter at Triple A, he said he knew he “easily” could have had a major league career. But Richards discouraged other teams from signing him, Durham said, by erroneously claiming Durham had a drinking problem.

“I’d never done anything to the man,” Durham said, shaking his head sadly.

Richards died at age 77 in 1986.

Durham’s interview is an important historical artifact, chronicling what it was like for the majority of Black men who tried professional baseball in the 1950s. They faced racism everywhere, from fans, teammates, opponents and superiors. Durham persisted, he told me, because he expected no less, having grown up in segregated Newport News, Virginia, where his grandparents taught him how to get along with people. That and his genial nature helped him have a better second act in baseball; he worked in the Orioles’ front office for years in a variety of roles, mostly in community relations, but also as a minor league coach and hitting instructor.

“I’m not bitter,” he said.

The fact that his major league career never launched?

“It’s something that happened,” he said. “I had no control over it. Just one of those things.”

Keep reading with a 7-day free trial

Subscribe to The Bird Tapes to keep reading this post and get 7 days of free access to the full post archives.