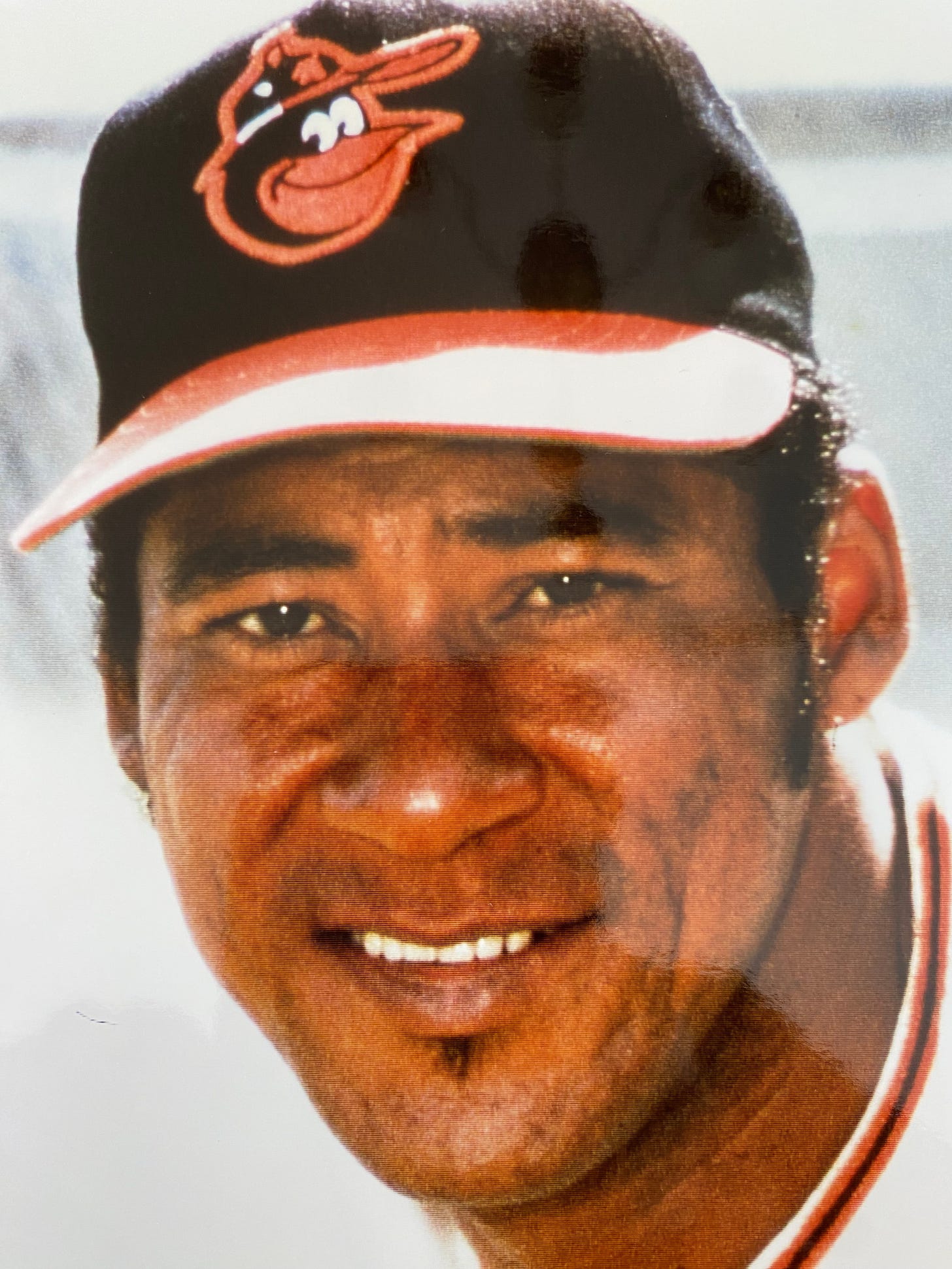

The Ace Who Came Out of Nowhere

The Orioles' acquisition of Mike Cuellar was a total steal that paid dividends for years. But when the deal was made, the success Cuellar would experience in Baltimore wasn't so easy to envision.

The Orioles’ acquisition of pitcher Mike Cuellar before the 1969 season is rightly considered among their shrewdest and most important moves. He immediately shot to the top of a rotation that gave the Orioles residence in baseball’s highest echelons for years. And the biggest piece they gave up for him was Curt Blefary, a former Rookie of the Year outfielder whose star was falling fast because he could only hit fastballs.

What a deal.

“It’s one of the all-time great trades. Cuellar was a terrific pitcher and the scouting had gotten wise to Blefary,” Orioles pitcher Dick Hall told me in 1999 in his interview for my book on Orioles history. (Spoiler alert: Hall’s interview is coming soon to the Bird Tapes and it’s a gem.)

Jim Russo, the Orioles’ top scout, was the one who proposed Cuellar as a trade target when no one else in the organization had seen him pitch. “He’s like an artist — he paints one side of the plate, and then he paints the other side of the plate,” Russo famously explained in an organizational meeting.

Orioles GM Harry Dalton actually negotiated with the Astros and made the deal, taking advantage of the fact that Cuellar had gone 8-11 for the Astros in 1968.

Cuellar’s turnaround was instantaneous. He went 23-11 for the Orioles in 1969 and ultimately won 143 games for manager Earl Weaver through 1976.

But success of that magnitude for Cuellar wasn’t guaranteed when the Orioles traded for him. His personal life was a mess, his pitching arsenal needed polishing and he was a lot farther down the road on his baseball journey than many realized.

He was already an old man, at least in baseball years.

Born in pre-Castro Cuba in 1937, Cuellar had signed with the Cincinnati Reds as a 20-year-old left-hander with natural command. But after he made a cup-of-coffee major league debut (two games) for the Reds in 1959, he disappeared, spending the next five years floating around the Mexican League and a series of minor league outposts as his contract moved from the Reds to the Detroit Tigers to the Cleveland Indians to the St. Louis Cardinals to the Houston Astros.

He finally established himself in the major leagues and had pitched regularly for the Astros for a few years when the Orioles acquired him, but he was about to turn 32 and had already thrown some 2,000 professional innings with relatively little to show for it. His major league record was 45-42.

He was no one’s idea of an ace.

But in Baltimore, Cuellar joined an organization that — in many ways — helped him realize his full potential.

He arrived with a two-pitch arsenal, a fastball that wasn't so fast anymore and a screwball, an effective off-speed pitch he’d developed in winter ball in the early ‘60s and wielded effectively in the majors. His curveball was nothing special. George Bamberger, the Orioles’ pitching coach under Weaver, worked with him to improve his curve, giving him a third pitch.

Bamberger and Weaver also held him to a higher standard. Cuellar was affable and popular, nicknamed Crazy Horse by teammates because he had so many superstitions. “Everything had to be exactly the same every time he pitched and please don’t interfere with his routine,” outfielder Paul Blair said in his Bird Tapes interview. But he also was mercurial and opinionated. He saw no need for the wind sprints Bamberger demanded of his pitchers on a daily basis. “He was a wonderful person, my wife’s favorite, but he didn’t want to run. I had to make him,” Weaver said in his Bird Tapes interview.

It helped that the Orioles had added a Spanish-speaking catcher, Elrod Hendricks, to Weaver’s platoon behind the plate.

“Elrod helped a lot with him,” Weaver said. “He helped me make it clear to Mike that he needed to run. Elrod spoke to him in Spanish, which was great because there’s a lot lost who you’re interpreting.”

Hendricks, in his Bird Tapes interview, said, “I had seen Mike in winter ball in ‘64 and ‘65, and he was throwing hard then, but without a breaking ball. When he came to us, he didn’t throw as hard, but he was a pitcher. He had that screwball, and Bamberger worked with him to develop a curve. We became roommates. We’d talk about how we wanted to pitch guys. We were on the same page. I knew exactly what he wanted to throw. I knew what I could go to if a pitch wasn't working. and he had confidence in me calling his game as a roommate. We had a good thing going.”

But the most important thing the Orioles did for Cuellar was help him clear up his personal life. He was in debt when he came to Baltimore.

“We found out Mike was in a bad marriage and beset with financial troubles. Apparently his wife was spending a lot of money and charging things all over Houston,” Dalton said in his Bird Tapes interview. “The conclusion was, ‘This guys’s just had so much on his mind that he can’t pitch up to his ability, but he’s got great stuff, and he knows how to pitch, and he’s smart, and we should get him.’

“After we made the trade, he came to spring training, obviously made the club and then came home to Baltimore and asked to borrow money. I said, ‘Tell me how much you owe and let’s see if we can help you out.’ So we sat down together and he brought his bills to me, and I went through them all. And he might have owed five thousand or six thousand dollars. He had about seven or eight accounts open. I said, ‘OK, let’s see what we can do.’”

Weaver, who’d worked in the loan business, told Dalton to call the parties Cuellar owed and see if they’d settle for less on the dollar.

“I called every one of those accounts and said, ‘Look, this fellow’s an employee, and he’s not in a position to pay you back. We can give you 10 percent if you want to take that, but this guy is not going to be able to solve this debt.’ And about four of them, right in that phone call, said, ‘OK, we’ll do that,’” Dalton said. “And then we worked with the others and finally got it down to about fifteen hundred or two thousand dollars that he owed. And he was able to pay that back. We advanced him enough that he could live and pay his expense. He was out of debt by the end of the year, and that was one of the biggest things for him, because he felt free again. In the meantime, he got divorced and married a schoolteacher and straightened himself out and then he could just concentrate on pitching and winning.”

Weaver said, “It made Mike a happy guy (to solve his money problems) and made him feel that, ‘Boy this is the place to be.’”

With his debts erased, a Spanish-speaking catcher to throw to, a new pitch to use, a great defense behind him and a powerful offense supporting him, Cuellar blossomed. He went 24-8 in 1970 and 20-9 in 1971. After falling just short of 20 wins in 1972 and 1973, he went 22-10 in 1974.

In other words, he fell just short of six straight 20-win seasons.

“With Cuellar, (Dave) McNally, and (Jim) Palmer, you could almost ring up 60 wins for us when the season started because each of them was going to win 20,” Blair said. “And with Cuellar and McNally, you never knew they were winning 10-0 or losing 0-10. They were the same guys. They were two really great left-handers, and the reason they were so great was they didn’t have the talent Palmer had. They didn’t have the 95 mph fastball Palmer had. They had to learn to pitch, know the hitters, hit corners, and they did it. And they never complained. Those kind of guys, you just die for. You break your neck to go out there and win for them.”

By 1976, Cuellar was no longer as effective — that year, he went 4-13 and lost his spot in the rotation. But his decline was hardly a surprise. He was nearly 40 and had thrown more than 4,000 innings as a pro. His time was up.

“He was indeed like an artist,” Palmer told the New York Times when Cuellar died of cancer in 2010. “He could paint a different picture every time he went out there. He could finesse you. He could curveball you to death or screwball you to death. From 1969 to ’74, he was probably the best left-hander in the American League.”

Like McNally,Miggy was another favorite back in the glory years. Watching righties try to hit that screwball was a lot of fun.

I never realized that Cuellar wasn't a great pitcher when the Orioles got him. Thanks for enlightening me!