THANK Youuuu, Rex Barney

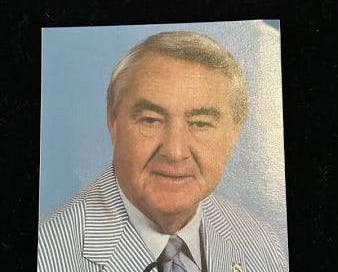

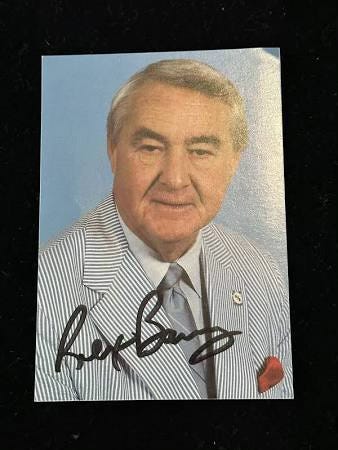

During his 24 years as the PA announcer at Memorial Stadium and Camden Yards, he became as essential to Baltimore's baseball culture as the bird on the Orioles' caps.

In 2025, from a distance of years, the story sounds wholly improbable — a well-known Brooklyn Dodger who never played for the Orioles becoming universally beloved in Baltimore and as ingrained in the city’s baseball culture as the birds on the Orioles’ caps.

But indeed, that’s the shorthand summary of Rex Barney’s singular place in the long chronicle of Baltimore baseball. His buttery voice and corny patter became the soundtrack of Oriole baseball during his 24 years as the public address announcer at Memorial Stadium and Oriole Park at Camden Yards.

Other master purveyors of his craft in his era included Yankee Stadium’s Bob Sheppard and Los Angeles’ John Ramsey, whose grave baritones suggested that their words hailed from a biblical mountaintop. Barney took a different approach. Although the Orioles were tough to beat, especially early in his PA tenure, the environment at their home games was more small town than big city, and Barney, a Nebraska native, fit right in, his PA tone as familiar and folksy as a favorite uncle at a family barbecue. He ended his deliveries by thanking the crowd for their attention, emphasizing the THANK in “thank you.” Most famously, whenever someone in the stands caught a foul ball, he lightheartedly announced, “Give that fan a contract!”

The fans ate it up, embracing his avuncular tone, which tacitly inferred that Baltimore was a place where fans were nice to each other and probably knew the person sitting next to them.

When he died at age 72 during the 1997 season, the Baltimore Sun wrote that Oriole games without Barney on the PA would be akin to “the national anthem never being played again.” Mike Flanagan, the former pitcher who had a knack for offering poignant perspectives, said, “His voice was almost like a security blanket. Being announced by Rex always gave me a quiet confidence, almost like the voice of a baseball god. He made you feel like everything would be alright.”

It was known in Baltimore that Barney had played for the Dodgers years earlier, but few knew just how remarkable his career had been, marked by a dazzling rise and spectacular flameout under the brightest of baseball lights. The drama seemed at odds with Barney’s genteel nature and soothing voice, but indeed, Barney had graced magazine covers at one point, before things fell apart.

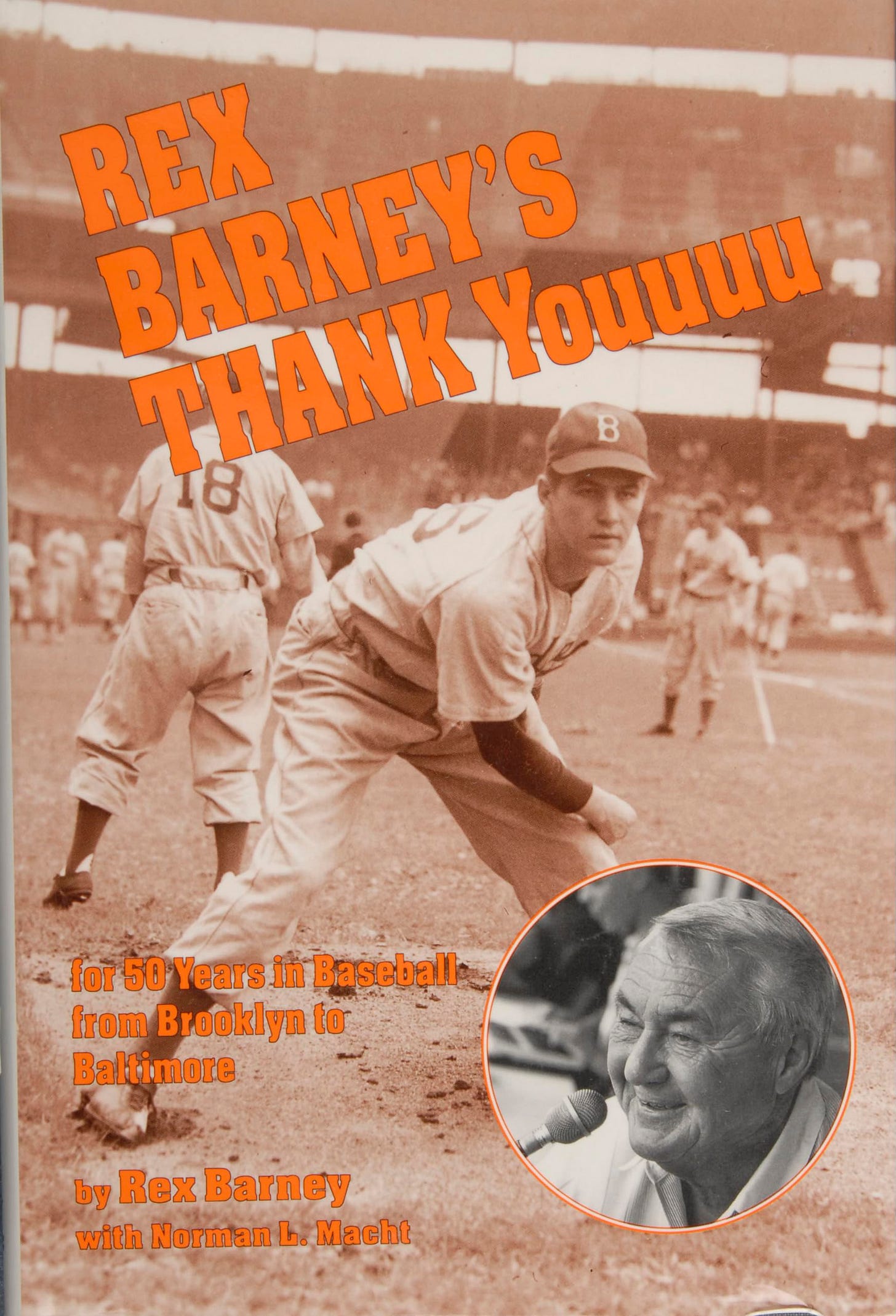

The Dodgers uncovered him in the early ‘40s when he was a high school star in Omaha. A powerful right-handed pitcher, he fired a fastball as hard as anyone had ever seen. The only problem was he didn’t always know where it was going. According to a Society of American Baseball Research profile of Barney, his first professional pitch soared five feet above the batter’s head, tore through a protective chicken-wire screen and conked a sportswriter on the head.

His arrival in Brooklyn was delayed by a stint in the Army in which he was awarded two Purple Hearts and a Bronze Star during World War II. Following his discharge, he earned a role with the Dodgers, who forever hoped he’d conquer his wildness and become dominant. When he started a World Series game against the Yankees in 1947, he walked 10 of the 32 batters he faced and took the loss, but he only allowed two runs and escaped one jam by getting Joe DiMaggio to ground into a double play with the bases loaded. His promise was evident for all to see.

Earning a spot in Brooklyn’s rotation at age 23 in 1948, he made 34 starts, won 15 games and tossed a no-hitter and one-hitter. But he walked 122 in 246 innings, and his propensity for wildness eventually got the best of him. Sportswriter Dick Young wrote that Barney would have made the Hall of Fame “if home plate was high and outside.” He threw his last major league pitch at age 25.

“I should have been up there with the greats,” Barney wrote in his autobiography. “I should have gone right up the ladder, but too many rungs were missing.”

He turned to broadcasting after he retired when Red Barber, the Dodgers’ legendary announcer, told him he had a pleasing voice and should consider a career in radio. That’s what brought Barney to Baltimore in 1965. Lee MacPhail, the Orioles’ GM at the time, had worked for the Dodgers when Barney played and helped him get a job as a talk show host. He began to fill in as the PA announcer at Memorial Stadium and assumed the job full-time when Bill Bolling departed in 1973.

Soon enough, it became impossible to imagine Oriole games without him.

“He was iconic. Everyone loved hearing him say, ‘Give that fan a contract,’ and ‘THANK you.’ That voice, that friendly delivery, those catch lines made him stand out. He wasn’t just a PA announcer. You knew who he was,” said Gary Davis, a 1980s-era WBAL radio producer who’d attended Oriole games as a fan when he was younger.

Davis and several other young producers worked on a WBAL talk show that Barney hosted — a sidelight he maintained during his run as the PA announcer.

“We (producers) were all basically fresh out of college and broke, and Rex would show up at the station every time with full meals for us — chicken and fries and boxes of Berger cookies,” Davis recalled. “The age gap didn’t matter. He just hung out with us. A lovely guy. He’d been in the war and pitched in the World Series but he never told stories about himself. You had to ask him to get him to talk about it.”

Barney’s talk show provided another bridge for him to connect with the fans.

“Unlike other talk radio, there was never any attitude or raised voices. He never insulted his audience or tried to bait them into calling. He genuinely welcomed everyone,” Davis said. “It was just someone who truly loved baseball, loved the Orioles and loved talking to people. I think adult listeners who wouldn’t call other talk shows felt comfortable calling Rex because they knew they’d be treated with respect and appreciation. And especially kids. When asked why he let kids call in, he simply replied, ‘Why wouldn’t I?’ I’m sure he loved their enthusiasm for the Orioles and was happy to nurture it.”

His PA work remained his principal connection with his adopted hometown. Barney’s daily routine never wavered. He’d arrive at the ballpark hours before the first pitch and immediately go down to the clubhouses to get the lineups and visit with the players and managers. “He was always there for me, so easy to talk to, like having my own shrink,” Jim Palmer recalled. “He was so gentle, compassionate and kind.”

Before the game, he’d settle into his chair overlooking the field and, in his mind, start his nightly conversation with what he considered his baseball family.

His routine endured despite a series of health issues that included a stroke in 1983, a heart attack in 1991 and the amputation of a leg in 1996 due to circulatory problems related to diabetes.

Davis visited him in the hospital the day after the amputation. “He was already up and walking; the physical therapists were shouting ‘Slow down, Mr. Barney!’” Davis recalled, chuckling. “He had a great attitude. It could’ve been depressing but he appreciated everything he had.”

The city was heartbroken when Barney died on August 12, 1997. He’d been due to work a game at Camden Yards that night. Flags at the ballpark were lowered to half-staff. Chuck Thompson led an on-field ceremony honoring his memory. The PA microphone went silent; batters walked to the plate unannounced. It felt right. More than a few fans wondered, “How in the world can anyone else do Rex’s job?”

Davis attended the funeral several days later. “The church was packed,” he recalled. “I’ll always remember coming out and seeing crowds of people on the sidewalks wearing Oriole shirts. They’d just come to pay their respects to Rex. It was amazing. He was such a nice guy. I was glad to see people show up for him. He deserved it.”

Thanks for this. Brings a nostalgic tear to my eye.

Memories of Memorial Stadium - vendors selling sodas with the cellophane on top, the masterful job the parking attendans did at the local school where my dad liked to park, "Ed-die, Ed-die" chants, and Rex Barney's "Thank youuuuuu".