Spirit of '66: Wally Bunker

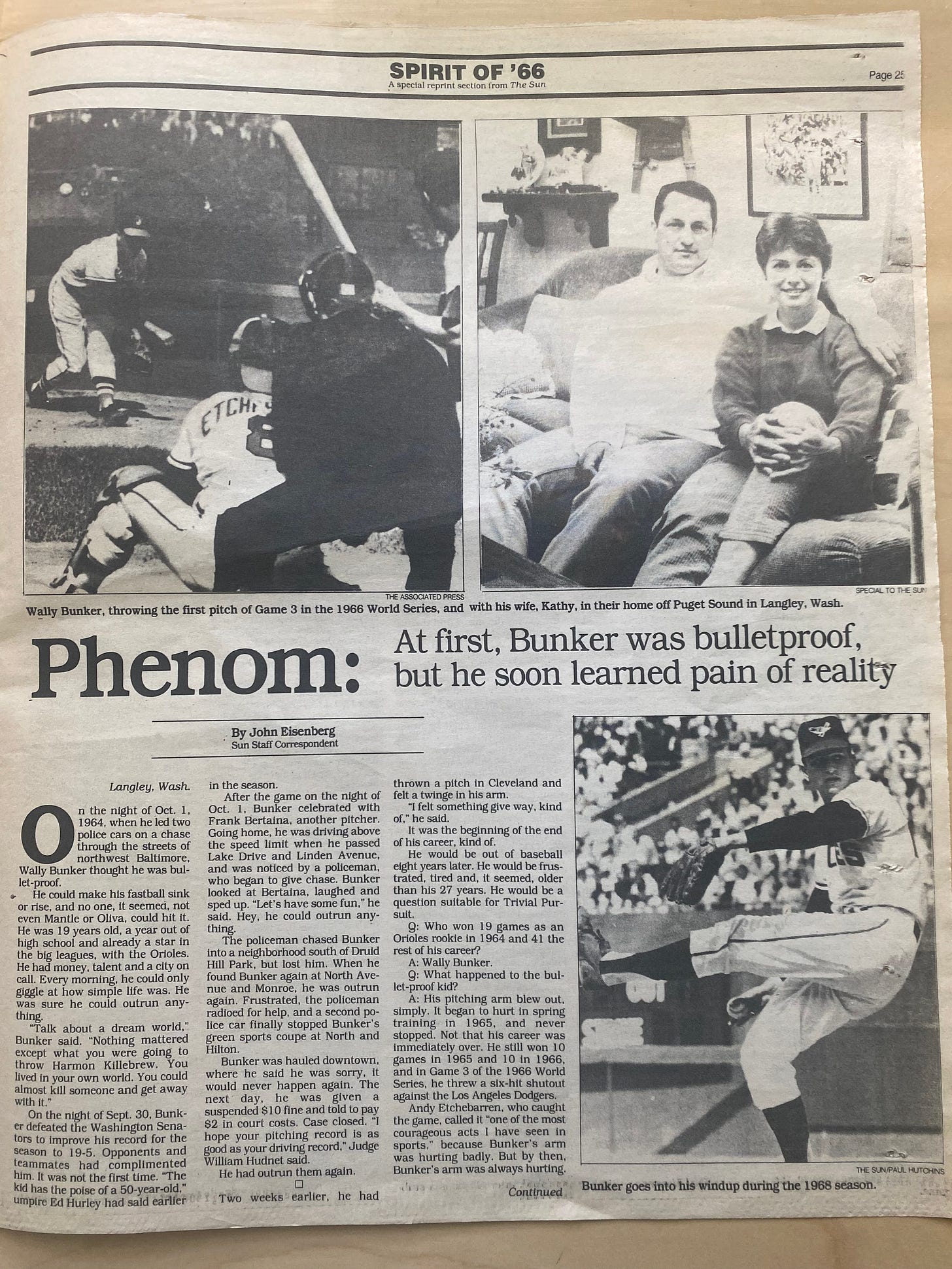

Arm pain curtailed his promising career, but it didn't stop him from throwing a gem in the most important start of his career -- Game 3 of the 1966 World Series.

When I sat down for an interview with Wally Bunker in the Pacific Northwest in 1986, having taken a plane, car and ferry to get to him on an island off the coast of Washington state, I was struck by how young he was.

To commemorate the twentieth anniversary of the Orioles’ first World Series title, the Baltimore Sun was sending me around the country to visit with players from the 1966 team, find out what they were doing and see what they recalled about that season. My stories eventually became a series titled “Spirit of ‘66.”

Naturally, the players were no longer as young as we recalled in our minds’ eyes. Frank Robinson was 50, as was Moe Drabowsky, the relief pitcher whose stellar outing in Game 1 of the World Series had keyed the Orioles’ stunning sweep of the Los Angeles Dodgers. Luis Aparicio was 52. Brooks Robinson was 49. Stu Miller was 58. Dick Hall was 55.

Bunker? He was just 41.

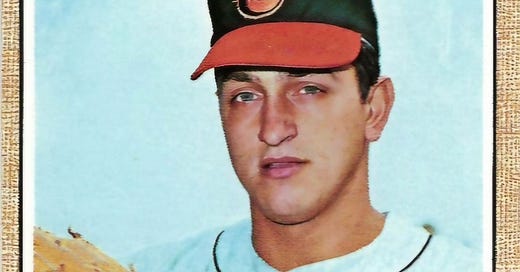

I did the math. He’d been all of 21 when he tossed a shutout to win Game 3 against the Dodgers at Memorial Stadium. And that meant he’d been, yikes, just 19 when he won 19 games for the Orioles in 1964, seemingly announcing himself as a major star.

The Orioles signed and developed a passel of excellent pitchers in the early 1960s, including Jim Palmer, who wound up in the Hall of Fame; Dave McNally, who wound up winning 181 games for the Orioles; and Dean Chance, whom the Orioles lost in an expansion draft and wound up winning a Cy Young award. Bunker belonged in their company as far as talent and potential.

It was almost as if he’d come out of a pitching laboratory, according to Harry Brecheen, the Orioles’ pitching coach in that era. A right-hander from San Bruno, California, Bunker had a powerful arm, great command of an array of pitches and “the perfect temperament,” Brecheen said. “It was like he was made to be a pitcher.”

When we spoke in 1986, Bunker didn’t dispute the high praise. “I was good (growing up); I never lost, honestly,” he said. “What can you say? I was blessed with great talent.”

But as I wrote in my story on Bunker in 1986 — presented audiobook-style below with me narrating — the magnificent arm that carried Bunker to the majors also let him down. He began to experience pain at age 20, in 1965, and never pitched again without pain. The Orioles exposed him and lost him in an expansion draft after the 1968 season, and he threw his last pitch in the majors at age 26, having won 60 games during his career — almost a third of them in that 1964 season when his future appeared limitless.

Whether he’d thrown too many innings for a 19-year-old that season was still being debated 20 years later, but regardless, when I interviewed him, Bunker expressed not an ounce of bitterness about having failed to realize his full potential. “I could have been great, and I know it, and that’s good enough for me,” he said.

It surely helped that he’d delivered magnificently in by far the most important start of his career. The Orioles had won the first two games of the 1966 Wold Series and counted on Bunker to help them maintain that momentum in the first Series game ever played in Baltimore. They only gave him a single run of support on a home run by Paul Blair in the fifth inning, but that was enough as the Dodgers barely mounted a threat over nine innings against Bunker.

“I told him afterward, ‘You’re not that good,’” teammate Steve Barber recalled in his Bird Tapes interview.

The Orioles’ catcher that day, Andy Etchebarren, called it “one of the most courageous acts I’ve seen in sports.” Bunker’s arm was hurting badly. A trainer wrapped it in hot towels between innings, leaving it red and blistered. But Bunker rolled through nine commanding innings, striking out six and walking just one. The Orioles completed their sweep of the Dodgers the next day.

Twenty years later, he and his wife were running a business selling, of all things, refrigerator magnets. Profits were rolling in. He was a long way from Baltimore and a long way from his baseball days, but he was busy and content.

“I would not change a thing,” he told me.

Here is my 1986 article about Bunker, read by your truly:

What could have been. I guess TJ surgery was 20 years to late for him. But he and any of us Orioles fans old enough to remember will always have that game 3 of that WS. Thanks always to Wally Bunker.