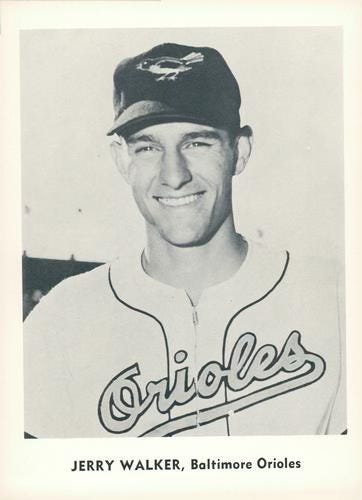

Lost Voices: Jerry Walker

One of the Kiddie Corps pitchers who helped launch the Orioles as contenders, he had a career that almost sounds like baseball-style science fiction today. Seriously, a 16-inning appearance?

For an example of how much the baseball industry has changed since the Orioles were in their infancy in the 1950s, Jerry Walker’s career is hard to top.

Hearing the details in 2024 truly boggles the mind.

In the spring of 1957, Walker was a star pitcher at Byng High School in Ada, Oklahoma, good enough to draw the interest of pro scouts. He signed with the Orioles for more than $4,000, an amount that officially designated him a “bonus baby.”

It meant he had to go straight to the major leagues.

Walker graduated from high school on June 28, 1957. Eight days later, he pitched for the Orioles against the Red Sox at Fenway Park.

Not surprisingly, he wasn’t ready. The Orioles trailed, 6-2, when manager Paul Richards put him in to start the bottom of the seventh. Walker walked the first batter he faced. Then he walked the second batter he faced. When he threw a wild pitch to the third batter, Richards pulled him.

When both of his baserunners eventually scored, Walker was left with an earned run average of infinity after his first pro appearance.

Welcome!

The idea of the bonus baby rule, in effect from 1947 until the amateur draft was instituted in 1965, was to keep the wealthiest teams from signing all of the best prospects. But the rule ruined countless careers by forcing young players to become major leaguers long before they were ready. When Walker signed, a player had to spend two seasons in the majors if he signed for more than $4,000.

The Orioles spent a ton of money on young bonus babies who didn’t pan out, including Bruce Swango, another pitcher from Oklahoma who had averaged 17 strikeouts per game in high school but, it turned out, couldn’t play in front of crowds. He was released nine weeks after he signed, with the Orioles owing him $36,000.

Walker fared better. A tall right-hander, he had a mix of pitches, good control and a level head. By September of his rookie season, he was effective enough to throw a four-hit shutout against the Washington Senators — yes, just over two months removed from his high school graduation.

In his 1999 interview for my book on Orioles history, conducted on the phone, Walker was positive about his unusual start in pro baseball.

“Baltimore was the only club willing to give me more than $4,000, so I signed and spent the (‘57) year there. There was a lot of talk that other clubs in prior years had given players money under the table to get around the $4,000 rule. Or gave their parents a job or whatever. I just went to Baltimore, worked out, came home and signed.

“We started working. I threw a lot of batting practice and pitched when games got out of hand. I started a game in August and didn’t get through the first inning. Finally I started throwing the ball around the plate. In September, I got to start another game, and I got my first win. If there was resentment (from veterans), I didn’t perceive it. They were very helpful. Connie Johnson and Skinny Brown, Billy Loes, Billy O’Dell. All those guys were extremely helpful. I’d heard about older guys (not helping young players), but to me, they were very helpful.

“They did away with the $4,000 rule in ‘58 and I went to Knoxville, Class A, and had a very good year. I was 18-4. My time in the big leagues helped. Had I signed and gone to the minors, I don’t think I would have had that kind of a year. I came up to Baltimore and pitched at the end of the year, and then I made the club in ‘59.”

As a 20-year-old in 1959, Walker was in the Orioles’ starting rotation with O’Dell, Brown, 36-year-old Hoyt Wilhelm and Milt Pappas, another 20-year-old bonus baby. Although Pappas led the team in wins, Walker pitched so well early in the season that he was the starting pitcher for the American League in the second All-Star Game played that summer. When he threw the opening pitch to Yogi Berra in the Los Angeles Coliseum, he became the youngest pitcher ever to start an All-Star Game, and after allowing a run on two hits over three innings, he earned the win.

When other young pitchers such as Chuck Estrada, Jack Fisher and Steve Barber joined Pappas and Walker in Baltimore, the Orioles suddenly had a strong, young staff. It appeared Walker would have a primary role.

On September 11, 1959, he started the second game of a doubleheader against the White Sox at Memorial Stadium. Fisher had thrown a shutout in the opener. When Walker also threw nine shutout innings in a scoreless contest, Richards kept him in. He wound up throwing 178 pitches over 16 shutout innings. The Orioles finally scored in the bottom of the 16th to give him the win.

It was an unforgettable triumph, but some observers believed Walker paid a lasting price for throwing so many pitches in one game. He was the Orioles’ Opening Day starter in 1960 but won just three games that season. In April 1961, he was traded to the Kansas City Athletics. He never had another winning season after his 16-inning appearance.

Walker had a keen mind for the game, helping him fashion a long post-playing career as a minor league manager, coach, scout and front office executive. When I interviewed him for my book on Orioles history in 1999, he was 60 years old and working as the St. Louis Cardinals’ director of player personnel.

He didn’t subscribe to the idea that his 16-inning appearance ruined him.

“I wasn’t throwing a lot of pitches that night (in 1959). Gave up six hits, walked a couple of guys, wasn’t in trouble much. They started checking me every inning after the tenth, asking, ‘Are you all right?’ I said fine. In the thirteenth or fourteenth, they let me hit, so I kept going. When I came in from the top of the sixteenth, Richards said, ‘That’s it, no more.’ Then Brooks drove in a run to win the game. I didn’t think 178 pitches was that much for 16 innings. I won’t say that it didn’t make me sore more than I was used to, but I felt fine. I didn’t have any problems. I was very sore the next day, but it was normal soreness. I got an extra day’s rest.

“I think they were conscious of my wellbeing. A lot of people made a big to do and said I hurt my arm and was never the same. After I got traded, Paul came over before a game and said to me, ‘I don’t think I’ll ever let a pitcher go that many innings again.’ But he also said, ‘I thought you were throwing good.’ The thing was, I didn’t want to come out, and I don’t think I would now.

“In and of itself, I don’t think it hurt. I came back the next year had some allergy problems and was never strong. But it wasn’t my arm. My arm didn’t hurt until the next year. Plus, we had a bunch of other pitchers going well, and I just didn’t pitch as much. My arm was fine. I don’t think you can tie that game to my arm problems at all. That only came after I was traded to Kansas City. I started out 7-2 in ‘61 but then I had elbow problems and later shoulder problems.”

Walker died at age 85 earlier this week, soon after Corbin Burnes became the latest Orioles pitcher to start an All-Star Game. (There haven’t been many.) It is interesting to contemplate how his career would have unfolded if Richards hadn’t asked him to go 16 innings in a single appearance. But the game was vastly different in 1959, as Walker’s career exemplifies in so many ways.