Lost Voices: Connie Johnson

A new Bird Tapes feature highlighting my Orioles history book interview subjects from a quarter-century ago whose comments, unfortunately, were not preserved on tape.

By the time I finished interviewing sources for my book on Orioles history a quarter-century ago, I had spoken to nearly 90 players, former players, managers, executives, scouts and broadcasters (and one owner) from the franchise’s first four-plus decades. But not all of the conversations were recorded and preserved on tape.

Out of necessity, I spoke to some sources on the phone. Lacking the technology to record those conversations (I know, I know, hard to believe now), I sat at my computer and fast-typed the source’s comments while we spoke. It wasn’t ideal, but it was the best I could do in a world without Zoom or other digital solutions.

I was able to use the phone interviews in the book, greatly enhancing it. But obviously, those interviews won’t be part of the Bird Tapes all these years later. You can read what the sources said in the book, but their voices, the actual sounds, have been lost.

It’s too bad, but the least I can do is shine a spotlight on some of my phone interview subjects as part of this deep-dive into Orioles history.

When I spoke to Connie Johnson in the fall of 1999, he was 77 years old and long retired from his post-playing career as an inspector at a Ford Motor Company plant outside Kansas City. It had been more than 40 years since he threw a pitch in the major leagues. He would live another five years.

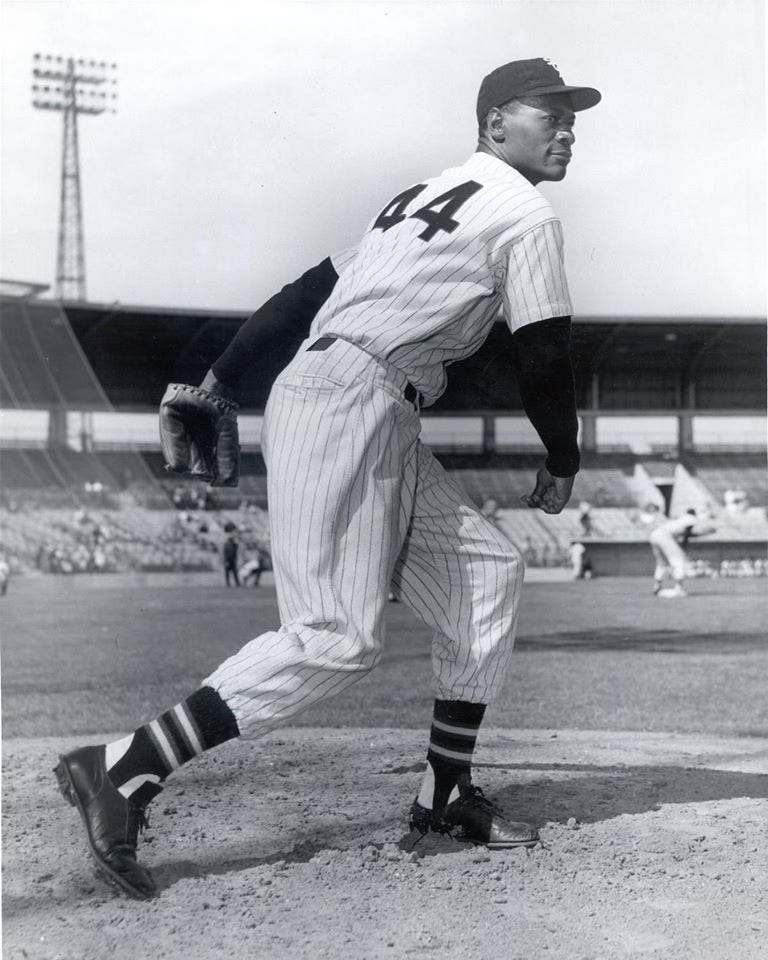

One of the Orioles’ first Black players, he had been a key member of their starting rotation for a few years after they acquired him in a trade with the Chicago White Sox in May of 1956. Paul Richards, the Orioles’ manager, had been the Sox’s manager earlier in the decade and liked how Johnson commanded his fastball. Johnson hadn't earned a prominent role in Chicago partly because he’d been tipping his pitches, an issue Richards promptly corrected once Johnson was in Baltimore.

In 1956, Johnson started 25 games for the Orioles, posted a 3.43 ERA and led the team in strikeouts. “The best right-hander in the league,” Richards called him. In 1957, he tossed three shutouts and won a team-high 14 games, a performance that earned him Baltimore’s Opening Day start in 1958. But he didn’t pitch as well later in 1958 and then he was gone as the Orioles turned to a group of younger pitchers, including Milt Pappas and Steve Barber.

It was not an easy time for Black pitchers in baseball. Although Jackie Robinson had broken the color line with the Brooklyn Dodgers a decade earlier and the sport was opening up racially, however slowly, it seemed front offices were more open to using Black position players than pitchers. Charlie Beamon, another Black pitcher who was on the Orioles in the 1950s, told me in his book interview, “I think it was like the Black quarterback thing later in pro football. Teams didn't really trust Black pitchers.”

In our phone conversation in 1999, I asked Johnson mostly about his time with the Orioles and his experiences in Baltimore. He told me:

“The Baltimore fans were great. I got along great with them. I lived off Reisterstown Road. There weren't any Blacks up there, but the people were nice. They took care of my kids. After I’d won 14 games in 1957 (the Orioles) wanted to give me a new contract about a month before the season was over. There was a little raise. I was making $10,000 and they wanted to give me $15,000. That was a pretty good raise at that time, but they were trying to sign me before I won any more games. After that, I didn’t try to lose no more games, but I didn’t try that hard, either. We couldn’t win the pennant and I had my money.

“Richards was all right at times. He was kind of smart in the way he’d do things. He’d get a pitcher and do something with him. He knew a lot about baseball. I don’t think he liked Blacks too much. He’d hide it in ways you wouldn't notice if you didn’t come looking for it. But I noticed. One time he wouldn’t let me pitch and told everyone my arm was sore. My arm wasn't sore. I don’t think they wanted me to win too many games. One sportswriter asked me, ‘When are you going to pitch again?’ I said my arm wasn't sore. Richards read that and said, ‘Don’t talk to sportswriters, they make stuff up.’”

It was interesting, but in limiting my interview to those subjects, I missed out on the aspects of Johnson’s career that make it so unusual and interesting decades later. I mean, he’d served as an honorary pallbearer at Satchel Paige’s funeral, for crying out loud.

Born and raised in Georgia, Johnson threw so hard and accurately as a youngster that he was being paid to play baseball by age 18. That was in 1940, seven years before Robinson integrated the major leagues. Other than his three-year stint in the military during World War II, Johnson spent most of the 1940s — probably his best years as a pitcher — with the Kansas City Monarchs, a top team in the Negro leagues. Still throwing hard, he teamed and barnstormed with Paige, won a lot of games and made All-Star teams. He was in the upper echelon of pitchers in the Negro leagues.

The White Sox signed him in 1952 and he made his debut with them a year later as a 30-year-old rookie. He was the thirty-first Black player to appear in the majors.

By 1955, he was in Chicago’s rotation. But his best years in the majors came after the Sox traded him to the Orioles and he flourished under Richards.

In a Society of American Baseball Research profile of Johnson, Buck O’Neil, the Negro leagues legend, who managed Johnson in Kansas City, said, “Connie was a good pitcher in the major leagues but he was a great pitcher in the Negro leagues. No comparison. He threw hard for the Monarchs. Hard. He had good control Could have won 20 games in the big leagues. Oh, yeah. Could have won 20 games every year. That’s Connie Johnson.”

Hello John. Thanks for your interview and writeup about Connie Johnson. I always wondered about his earlier career before the Orioles and I wondered back in 1958 and 1959 looking over his Topps cards during those years why he had not played in the majors longer. I was very ignorant about black players' plight regarding Major League Baseball when I was 7 and 8 years old. Mark Millikin