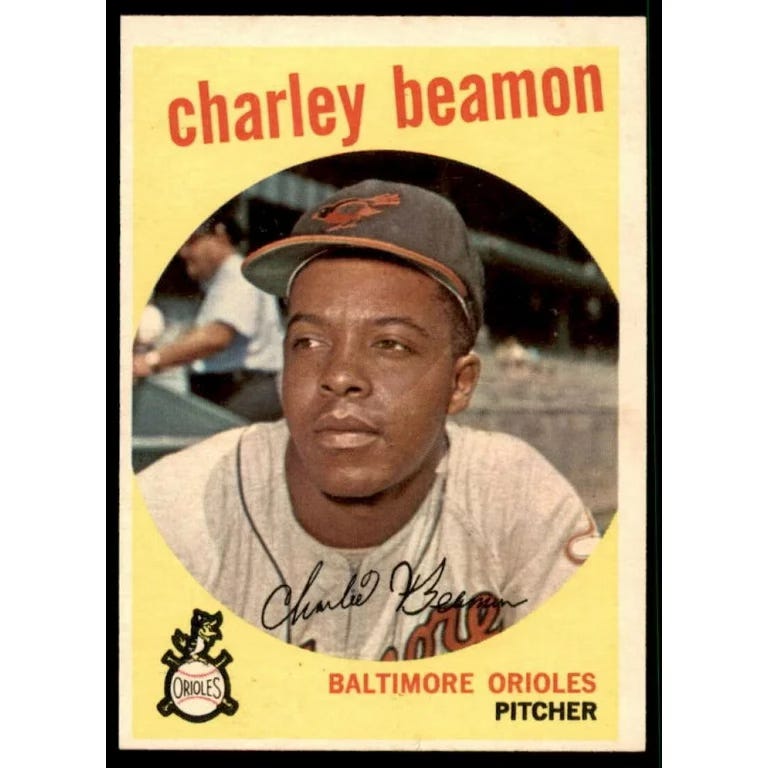

Lost Voices: Charlie Beamon

As the youngest-ever Black pitcher in the major leagues at the time, he shut out the Yankees in his debut. But his career with the Orioles never launched, and years later, he was sure he knew why.

(One in a series of articles highlighting former Orioles whom I interviewed for my oral history a quarter-century ago, but only on the phone, depriving me of a recording I could play now as part of the Bird Tapes.)

The Orioles quietly — very quietly — made history when they started a 21-year-old pitcher named Charlie Beamon against the New York Yankees on a windy Wednesday afternoon at Memorial Stadium near the end of the 1956 season.

Beamon became the youngest Black pitcher to perform in the major leagues in the near-decade since Jackie Robinson crossed the color line in 1947.

A steady but small trickle of Black players had followed Robinson into the majors in the late ‘40s and early ‘50s, but most played in the infield or outfield. Teams were nervous about putting Black players at pitcher or catcher, the so-called “thinking” positions, where, it was believed, a sharp mind was needed as much as a stout body.

“I think it was like the Black quarterback thing later in pro football. Teams just didn’t trust Black pitchers, especially young Black pitchers,” Beamon told me when I interviewed him in 1999 for my book on Orioles history.

Indeed, most of the first wave of Black pitchers in the majors were veterans who’d experienced the Negro leagues, giving them a track record, unlike youngsters such as Beamon. “Don Newcombe, Joe Black, Connie Johnson, Satchel Paige,” Beamon said, listing the top Black pitchers who’d preceded him. “I was just 21. There was no one like me.”

In the early ‘50s, Beamon had starred in sports at McClymonds High School in Oakland, California, alongside Frank Robinson, destined for baseball’s Hall of Fame, and Bill Russell, destined for basketball’s Hall of Fame. It was heady company, but Beamon made just as many headlines.

“He had really good stuff, a great arm. He should’ve been a good major league pitcher,” Robinson told me in his Bird Tapes interview.

Turning pro, Beamon continued to impress scouts while pitching for the Oakland Oaks of the Pacific Coast League, and his path to the majors materialized when the Oaks and Orioles signed a working agreement. In 1956, the Oaks moved to Vancouver and Beamon won 13 of 19 decisions. The Orioles called him up in September.

When Beamon strode to the mound for his major league debut against the Yankees on September 26, 1956, some 7,000 fans were salted around Memorial Stadium. The Orioles were buried in the American League standings and the Yankees had clinched the pennant. (They would win the World Series in a few weeks.) But the Yankees didn’t dismiss the game. Their lineup included Yogi Berra, Enos Slaughter, Bill Skowron and Billy Martin. Their starting pitcher was Whitey Ford, going for his twentieth win of the season.

Pitching to Gus Triandos, Beamon walked two batters in the top of the first, but emerged unscathed. He walked another batter in the second, but again retired the side without allowing a run.

“I was a little wild, but I had a lot going for me,” Beamon told me. “I was throwing a change-up, a curveball and a live sinker.”

The Orioles took the lead in the bottom of the third when Tito Francona scored on a wild pitch. Beamon settled in, retiring seven consecutive hitters at one point and stranding seven runners in the fifth, sixth and seventh innings combined.

Yankees manager Casey Stengel sent Mickey Mantle up to bat as a pinch hitter with two on and one out in the top of the seventh. He popped out.

Orioles manager Paul Richards gave Beamon a long leash, and despite dealing with steady traffic, Beamon reached the ninth and retired the side in order to secure the win. His debut couldn’t have gone better. He’d out-dueled Ford, the Yankees’ ace, pitching a four-hit shutout in a 1-0 victory. Although he walked seven, he struck out nine, seemingly quelling any doubts about whether he had major league stuff.

“What I liked most about him was his heart,” Orioles first baseman Bob Boyd said after the game. “It isn’t often you see a kid get behind (in counts) like he did several times and keep his nerve, especially if he’s playing the Yankees.”

Beamon was so excited that he danced in the dugout after the game. A few days later, he made another appearance, allowing two runs over four innings as the Orioles rallied to beat the Washington Senators.

His final stat line for the season was small but impressive — a 2-0 record with a 1.38 ERA over 13 innings — and off that, the media expected Beamon to pitch for the Orioles in 1957, perhaps as part of the starting rotation. Paul Richards, the club’s manager and GM, seemingly wasn’t opposed to using Black pitchers. He had acquired Connie Johnson, who became a mainstay in the rotation.

But ominously, Beamon didn’t pitch much in spring training in 1957. “Not as much as you’d expect from someone who’d pitch so well the year before” he said.

He started the year in Baltimore, but after allowing 16 baserunners in four appearances spanning eight innings, he was optioned to Vancouver for the rest of the season. Richard told reporters that he needed to polish his curveball and gain more confidence, but according to Beamon, the manager never spoke to him about it.

“He didn’t respect me enough to talk to me. He had his coaches come over and talk to me when I was sitting right next to him (in the dugout),” Beamon said.

In 1958, he made the club and stayed for the whole season, pitching to a 4.35 ERA over nearly 50 innings. But if he wasn’t the last man on the staff, he was close. “I’d go a month without an appearance. I think I started three games,” he said.

The Orioles parted ways with him after that season and he never pitched in the majors again. “I was out of baseball by 1960,” Beamon said. When we spoke years later, he believed he’d never stood a chance due to the prejudice against Black pitchers that prevailed in his era.

“I don’t know if it was the Orioles or Paul Richards,” Beamon told me. “I saw enough to know that, ability-wise, I had no problems. I saw (Black pitchers) better than me who didn’t make it or get as far as I did. Something bigger was in control. There wasn’t anything I could do, but to not even be considered or not even respected, that hurt more than anything.

“In the long run, I would’ve respected myself more if I’d spoken up, said my piece and gone home. My self-esteem was destroyed. I believed in the American Dream, that anything was possible. It took me years to get back up. As I got older, I understood what had happened and I got myself together and into a career, but I couldn’t for a long time. To be honest, I’d rather forget about my time in baseball.”

After baseball, according to a Society of American Baseball Research profile, Beamon worked for an organization that provided job training and job placement for the unemployed and underemployed. He was 65 years old when we spoke (he died in 2016 at age 81) and he was careful not to paint his baseball experience as entirely negative. He treasured his time with his Black teammates, especially Connie Johnson.

“Some wonderful things happened, the camaraderie and friendships I had with Connie, Bob Boyd and Joe Durham, those guys,” Beamon said, “and also, Lenny Moore with the (football) Colts. He was a superstar, but he talked to me and helped me. He was so down-to-earth and made you understand that we (Black athletes) were all in the same boat.

“The friendships and inspiration and togetherness I felt from those guys, I wouldn’t trade that for anything. You can have all that money they’re making now. One day, I was sitting in the dugout with Connie and I asked him, ‘Do you think I could’ve pitched in the Negro leagues?’ And he said, ‘Oh, yes, you could’ve done well.’ That meant more to me than beating the Yankees, knowing he thought I could do well. I almost started crying right there in the dugout.”

(Click here and here for other recent Bird Tapes posts commemorating Black History Month.)

Thanks for telling us about Charley Beamon, Sr., John. In 1955 with Stockton, Charlie posted a 16-0 mark with a 1.98 ERA. He pitched 139 innings, struck out 112 and walked 62 batters.

If Frank Robinson believes Charlie could have been a good major league pitcher, I believe it.

Great story but such a sad one. Timing is everything and in this case this young man was a number of years to early. Who knows what might have been.☹️