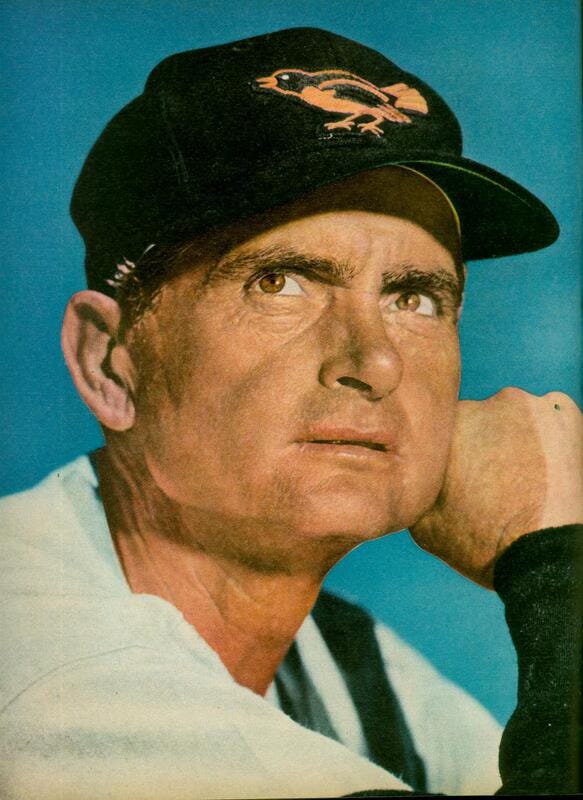

He Taught Earl Weaver How to Argue

The Orioles' iconic skipper learned a lot from Paul Richards, such as the importance of pitching and defense and, yes, just maybe, how to berate an umpire.

It seems like the easiest trivia question ever posed: Which manager of the Orioles barked and ranted at umpires so profanely and so relentlessly that he set records for being ejected from games?

It’s Earl Weaver, of course. Right?

The Orioles’ legendary manager is in the Hall of Fame mostly because he was so good at the job; among all major league managers with a thousand wins since Weaver took charge in Baltimore in 1968, his .583 winning percentage is the highest. But Weaver’s high place in baseball history is also due at least somewhat to his famously cartoonish arguments with umpires, which fans eagerly anticipated and roared about for years. They added a human element to the game that, alas, video replay has pretty much eradicated. (Yes, alas.)

If an Encyclopedia of All Sports existed, Weaver’s picture would surely go alongside the entry covering arguments with umpires in baseball. His 96 career ejections ranks fourth all-time behind Bobby Cox (162) John McGraw (121) and Leo Durocher (100), and Weaver managed far fewer games than those three.

He was good at getting tossed.

But here’s a shocker: Weaver actually doesn't even rank first all-time among Oriole managers in percentage of games in which he was ejected during his career.

He was tossed from 3.8 percent of the 2,541 games he managed, but Paul Richards, who managed the Orioles from 1955 through 1961, was tossed from 4.5 percent of the 1,837 games he managed for the Orioles and Chicago White Sox.

Richards was just as good as Weaver at getting tossed. (With 82 career ejections, he ranks eighth all-time.) He just didn’t manage for as long.

I spotted those surprising numbers in a chart that author John Miller included in his Weaver biography, The Last Manager, due for publication in March 2025. I recently read an advance copy and highly recommend it. I’ve written two books and thousands of articles about the Orioles, but there was a lot in Miller’s book that I didn’t know, especially about Weaver’s background, playing career and managerial influences.

In the book, Weaver cited three mentors as he developed his style — two of his managers in the minors and Richards, who was in charge of the Orioles’ baseball operation when Weaver first transitioned from playing to managing in the 1950s and began to rise through the ranks.

Richards’ important role in Orioles history has been chronicled here at the Bird Tapes. After ownership brought him in with nearly infinite power in 1955, making him both the major league manager and the GM, he upended the moribund franchise, made a million trades, spent a ton of money (some wasted) and eventually laid a winning foundation before he left in 1961.

He had a lasting influence on many people in the organization, including Weaver, who clearly learned from watching Richards operate. Richards believed in pitching and defense as the keys to winning. So did Weaver. Richards was ahead of the curve on statistics, putting faith in on-base percentage long before the rest of the game. Weaver also was well ahead of the curve on statistics, relying on individual pitcher-hitter matchup stats to maximize his lineup’s effectiveness.

Both were unafraid to tinker if it meant gaining an edge. Richard designed a special glove for his catchers to use to help them corral Hoyt Wilhelm’s knuckleball. Weaver pioneered the use of radar guns to help him assess his pitchers.

Given those many striking similarities, it’s hard not to speculate that Weaver also learned from watching Richards amble onto fields and blister umpires’ ears.

They were different in size and demeanor. Weaver was a loud, feisty bantam who cursed in casual conversation, and Richards was tall, lean and generally taciturn, a church-goer who routinely quoted scripture. But when he was angry at an umpire, he delivered rants so profane they shocked even his players.

In an interview for my oral history of the Orioles, From 33rd Street to Camden Yards, published in 2001, infielder Marv Breeding said, “He was one of the nicest guys, but when he went after the umpire, he said words I’d never heard before. He didn't just run out there, either. He’d wait an inning after something made him mad, and then he’d come out and you could pretty well bet he’d be gone. Maybe he waited to get his vocabulary straight. You never heard him say a cussword otherwise. He saved it for the umps.”

Joe Ginsberg, a reserve catcher on the Orioles in the late 1950s, told me, “He’d go up to the umpire and say, ‘Sir, do you know who I am?’ The guy’d say, ‘Come on, Paul, what?’ And Paul would say, ‘I’m the manager of this club, and not only am I the manager, I’m the general manager.’ He’d start slow and soft and just get loud and worse. His first couple of words would get him tossed. He was a very religious man, but he’d use unbelievable language, just incredible.”

Weaver had more of a sense of theater, no doubt. With his eyes bugged and his cap turned sideways, he’d race onto the field waving his arms and spewing insults, delighting the crowd. One time, famously, he brought a rule book onto the field to make his point.

When I spoke to Weaver for my book in 1999, I tried to get him going on the subject of his arguments with umpires, but he was long gone from the game by then, enshrined in the Hall of Fame and seemingly embarrassed about how he’d behaved.

“When you think you’re getting cheated and it’s going to cost you a ballgame, I wish I could have accepted it more, but I couldn't,” he said. “And then, when a player would get upset, you had to get out there because you didn’t want to lose a player. You had to get in between him and the umpire right away and do his arguing for him. That happened a number of times. Then something would be said, and the umpire would say something back and you’d lose your temper. Just stupid. The people enjoyed it, I know. But I hated it. Those incidents, I just hated them with a passion. They just happened. You couldn’t make it up. I hate seeing them on TV now.”

Seeking balance, I interviewed umpire Marty Springstead for my book; he and Weaver had battled for years. What was it like on the other side of the argument?

“He was just a pain in the ass, yelling from the dugout, screaming when he didn’t get a pitch,” Springstead said. “I don’t know how many times I threw him out. He says 11, I say 13. It wasn’t even fun after awhile. He wanted everything his way, and you don’t always get that. And sometimes he just wouldn’t listen to reason. That’s where we had most of our problems. Either he didn’t want to hear your side, or he didn’t believe it. He’d come out there with his cap turned, and he knew how to turn it so he could pop you (in the face) with it.”

But once they were retired, Springstead told me, he got along fine with Weaver to the point that he was invited to the ceremony the Orioles held for Weaver at Camden Yards before Weaver went into the Hall of Fame in 1996. On a sunny Sunday afternoon, there was a ceremony before a game and Weaver rode around the field in the back of a car, smiling and waving as the fans cheered.

Springstead’s story about that day made me laugh harder than any story I heard while researching my book on Orioles history.

“No one knows this, but I drove the car when he went around waving from the back,” Springstead said. “They’d invited me and somehow I wound up driving the car. And I had this thought, about halfway through, that I ought to slam on the brakes and send him sprawling over the back. Smack his little ass in the dirt back there. Then I’d turn around and say, ‘Earl, you got that coming. I owe you that.’ But it was his day, and I didn’t do it. I thought about it. The rest of the way around the field, I sat up there listening to the people cheering and thought, ‘I ought to slam on these brakes and send that little bastard flying.’”

Great story about Springstead driving the car.