Birth of the Oriole Bird

Dick Armstrong, an innovative young publicist, and Jim Hartzell, a newspaper cartoonist, were the key figures in introducing an image for the Orioles that still resonates seven decades later.

In terms of how they would present themselves to the world, the Orioles were a blank slate when they opened their offices in Baltimore in late 1953, months before their first game at Memorial Stadium the following spring. They’d come from St. Louis, where they were known as the Browns and played second fiddle for decades to the far more successful Cardinals. Now, in a new city, with a new nickname, they needed a fresh start.

It fell to an innovative, young publicist named Dick Armstrong to give the Orioles an image and sell them to the public.

Armstrong was a Baltimore native who’d attended the McDonogh School and Princeton, where he majored in economics and pitched for the baseball team. Shortly after his college graduation, he attended a major league game at Shibe Park in Philadelphia and introduced himself to Arthur Ehlers, a fellow Baltimore native who ran the Athletics’ farm department. Impressed, Ehlers hired Armstrong to help run one of the club’s minor league affiliates. (Armstrong briefly tried to forge a pro playing career, but after a forgettable minor league stint, he joined the front office.)

As noted in a Society of American Baseball Research profile of Armstrong, major league teams were just discovering the value of public relations after World War II. When the A’s opened up a job, Ehlers encouraged Armstrong to devise a plan for publicizing the A’s and apply. Connie Mack, the franchise’s venerable owner/manager, born during the Civil War, may have been skeptical about PR, but he was impressed with Armstrong. At age 25, Armstrong became the franchise’s first PR director.

The A’s didn’t win many games, but Armstrong utilized modern PR techniques to boost attendance. He conducted fan surveys, published a newsletter and yearbook and garnered headlines with stunts such as an official weigh-in for Bobby Shantz, a diminutive pitcher who won the American League’s MVP award in 1952.

When the Browns moved to Baltimore after the 1953 season, the new owners hired Ehlers as their general manager. They liked that he was from Baltimore. Ehlers only held the job for a year — the owners hired Paul Richards as manager/GM in 1955 — but he filled the front office with sharp, young talent such as Jim McLaughlin, Jim Russo, Joe Hamper and Harry Dalton. (Ehlers continued with the Orioles for another two decades, as Richards’ assistant and then as a scout, before retiring in 1973.)

Ehlers hired Armstrong as the Orioles’ PR director months before their inaugural season. Armstrong was 29.

“There was much to be done in establishing a new major league organization, especially when our new home, Memorial Stadium. was still under construction,” Armstrong wrote in a blog post years later. “An early priority was to develop a stylized Oriole for use on our baseball caps, stationery, and various concession items. We announced a contest, inviting local artists to submit their versions, the winner to receive a cash prize.”

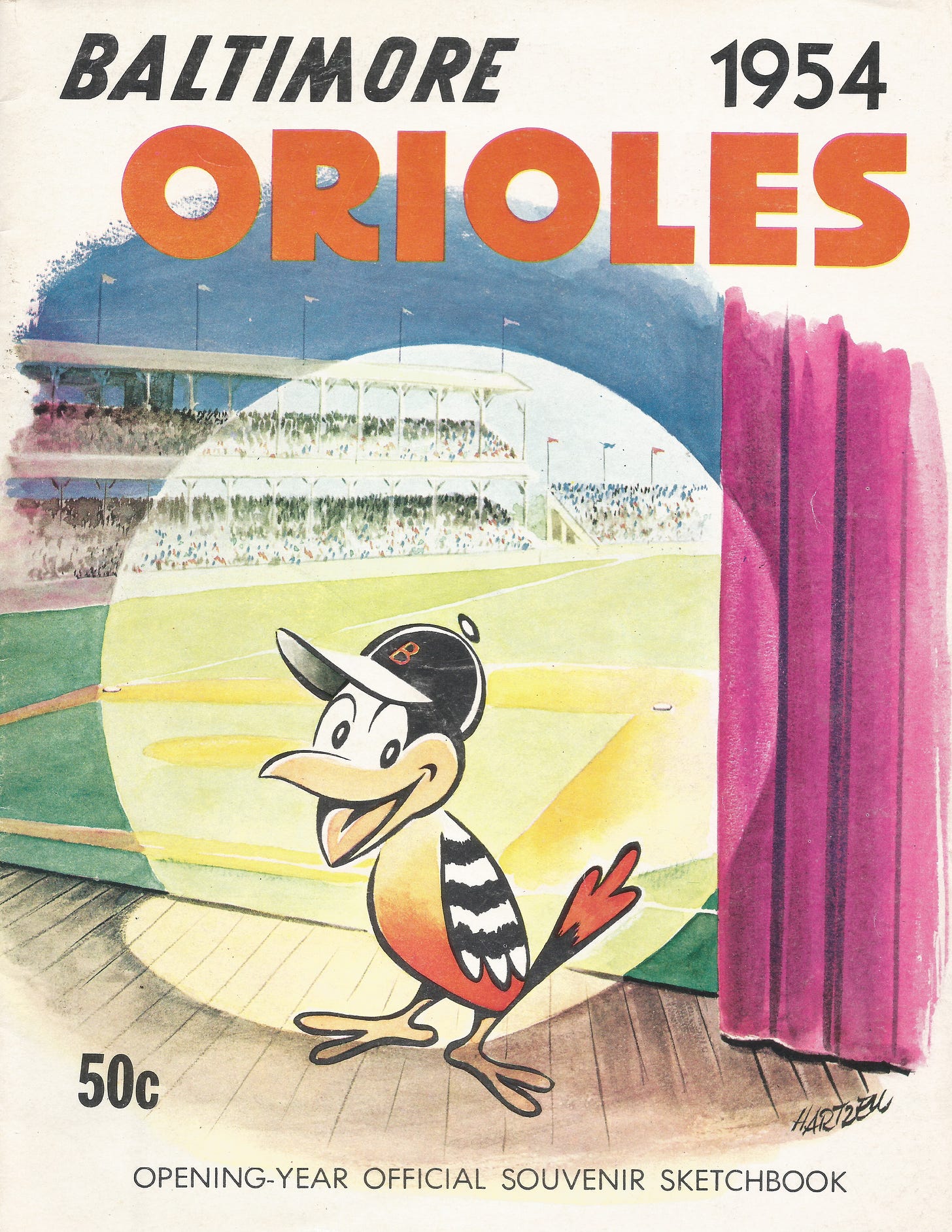

The club could have elected to utilize an orinthologically-correct Oriole as its emblem, as it did decades later, but Armstrong wanted a cartoon bird. “I was looking for a jaunty but likable bird, one with plenty of personality,” he wrote. “Several excellent entries were received. But one stood out above all the rest.”

The winning entry came from Jim Hartzell, a Baltimore Sun cartoonist. Armstrong unveiled the bird in early January 1954, months before the first game.

“We named our new mascot ‘Mr. Oriole’ and his perky face was quickly popularized,” Armstrong wrote.

Then Armstrong conjured an outside-the-box idea for the new team’s image.

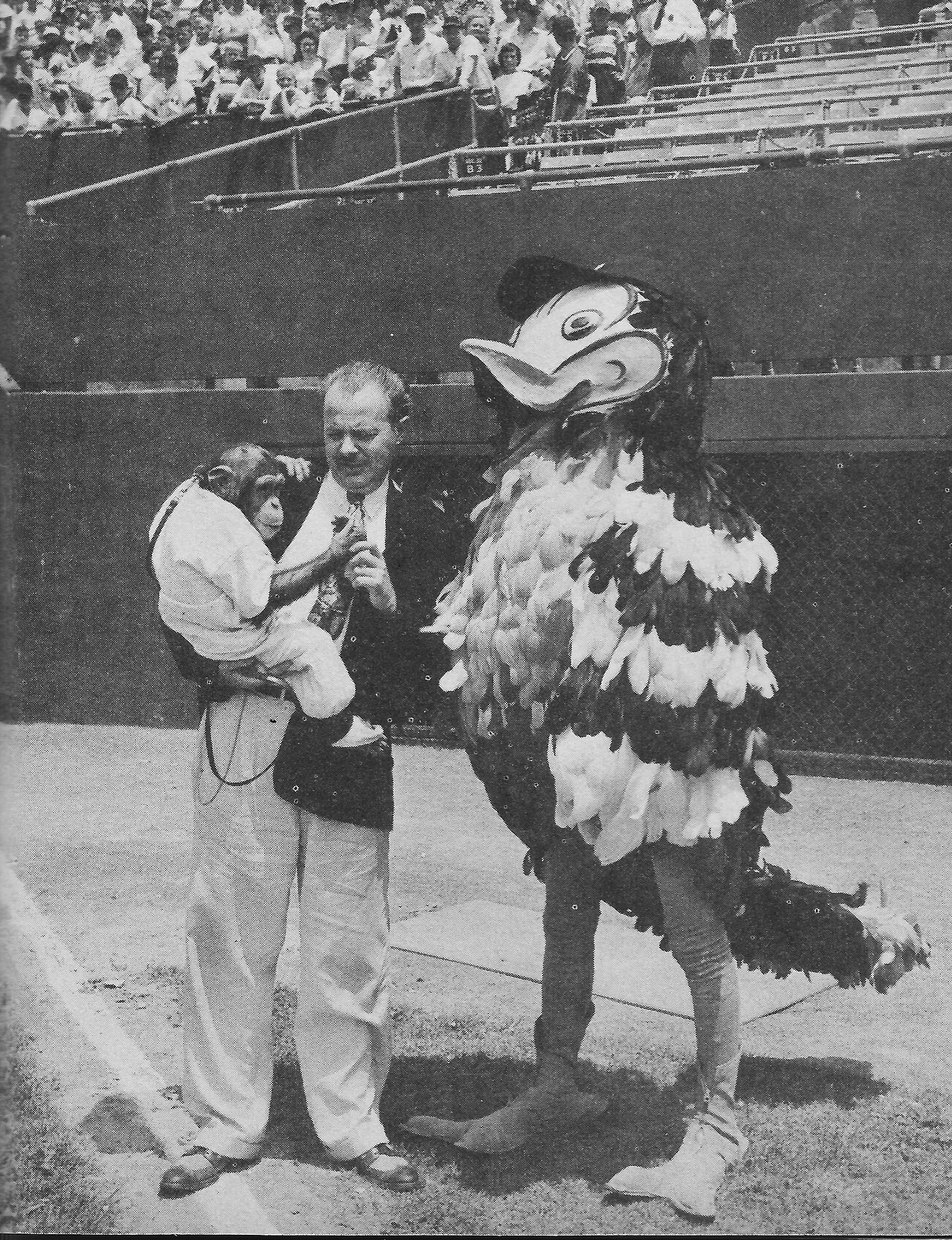

“I wondered if it would be possible to create a costume that would replicate the expression and appearance of Mr. Oriole, so that a three-dimensional version of the bird could cavort on the field and in the stands during games,” he wrote. “My high school friend and classmate Johnny Myers knew a costume designer whose name was Tinker — a relative of the famous Chicago Cubs shortstop, Joe Tinker. After examining the sketches of Jim Hartzell, Mr. Tinker excitedly accepted the challenge, and within a few weeks had produced a handsomely-made costume. I prevailed upon Johnny to be the first ‘Mr. Oriole’ because, as I jokingly put it, he had the legs for the part.

“Early in the 1954 season, when the strikingly colorful bird made his first public appearance at Memorial Stadium following a proper introduction over the public address system, the fans went wild. Mr. Oriole cavorted with the fans and the players to everyone’s delight, but the piece de resistance was when he whipped out from beneath one of his fathered wings a trumpet, which he could play through his beak. Johnny was an excellent jazz musician, and the effect was sensational! We had the only trumpet-playing bird in captivity!”

The Orioles struggled mightily on the field in their first season in Baltimore, finishing with a 54-100 record. But they drew more than a million fans, which was more than three times as many as the Browns had drawn in their final season in St. Louis. Armstrong’s PR efforts helped.

Armstrong also contributed in other ways to the notion that the nascent Baltimore franchise was a forward-thinking entity. Having studied scientific polling techniques in college and worked for George Gallup during the 1948 presidential election, he understood the value of information. With that in mind, he conducted what was believed to be the first fan survey ever taken at the major league level using scientific techniques. The Sporting News complimented the Orioles for their “wide-awake” approach to developing a lasting fan base.

Armstrong was a rising star in the baseball industry. But as noted in the SABR profile, his baseball career abruptly ended when he experienced a spiritual calling during Orioles spring training in Daytona Beach, Florida, in 1955.

According to SABR, “He received a personal calling to the ministry, which he described as his ‘Damascus Road Experience.’ He left the Orioles at the end of the 1955 season to study at the Princeton Theological Seminary. Armstrong spent the next 60-plus years, until his death in early 2019, as a pastor, educator, author, and missionary in the Presbyterian Church.”

But while his mind was on other matters, he retained an interest in baseball and steadfastly rooted for his hometown Orioles, recalling with pride his contributions to their start-up efforts decades earlier. He blogged with displeasure upon learning in 2012 that the Mascot Hall of Fame had identified Mr. Met, the mascot of the New York Mets, as the first live version of a mascot to appear at a major league game.

“WRONG! Ten years before Mr. Met or any other Major League mascot appeared, there was MR. ORIOLE! The Mets mascot was conceived in 1963 and made his debut in 1964. Mr. Oriole was hatched in 1954,” Armstrong wrote.

On August 8, 2014, when the Orioles celebrated their sixtieth anniversary in Baltimore, they invited Armstrong to throw out the first pitch before a game at Camden Yards. He was the only surviving member of the original front office. The former Princeton pitcher “somehow managed to get the ball over the plate,“ he wrote.

Hartzell, the cartoonist who drew the original bird, retired in 1979 after a 45-year career with the Baltimore Sun. Although the team has gone on to use numerous other cartoon birds during its seven-plus decades in Baltimore, as noted in a historical marker at Camden Yards (see below), Hartzell’s bird was where it all started.

In Hartzell’s latter years at the newspaper, his bird graced the front page every morning after the Orioles played, smiling happily if the team had won the day before and looking disconsolate if the team had lost. It was a familiar ritual of living in Baltimore and following the Orioles in the paper — you knew how they’d fared before you opened up the sports section.

In his final years before his death at age 93 in 2003, Hartzell would bring a folding chair to Towson University’s baseball games and watch on a hill overlooking the diamond, where Billy Hunter joined him. The shortstop on the Orioles’ first team in 1954, Hunter had a long career as an Orioles coach and managed the Texas Rangers before becoming Towson’s baseball coach and, eventually, the school’s athletic director. (My interview with Hunter is in the Bird Tapes archive.)

In retirement, Hunter and Hartzell enjoying sharing their memories from the Orioles’ first years.

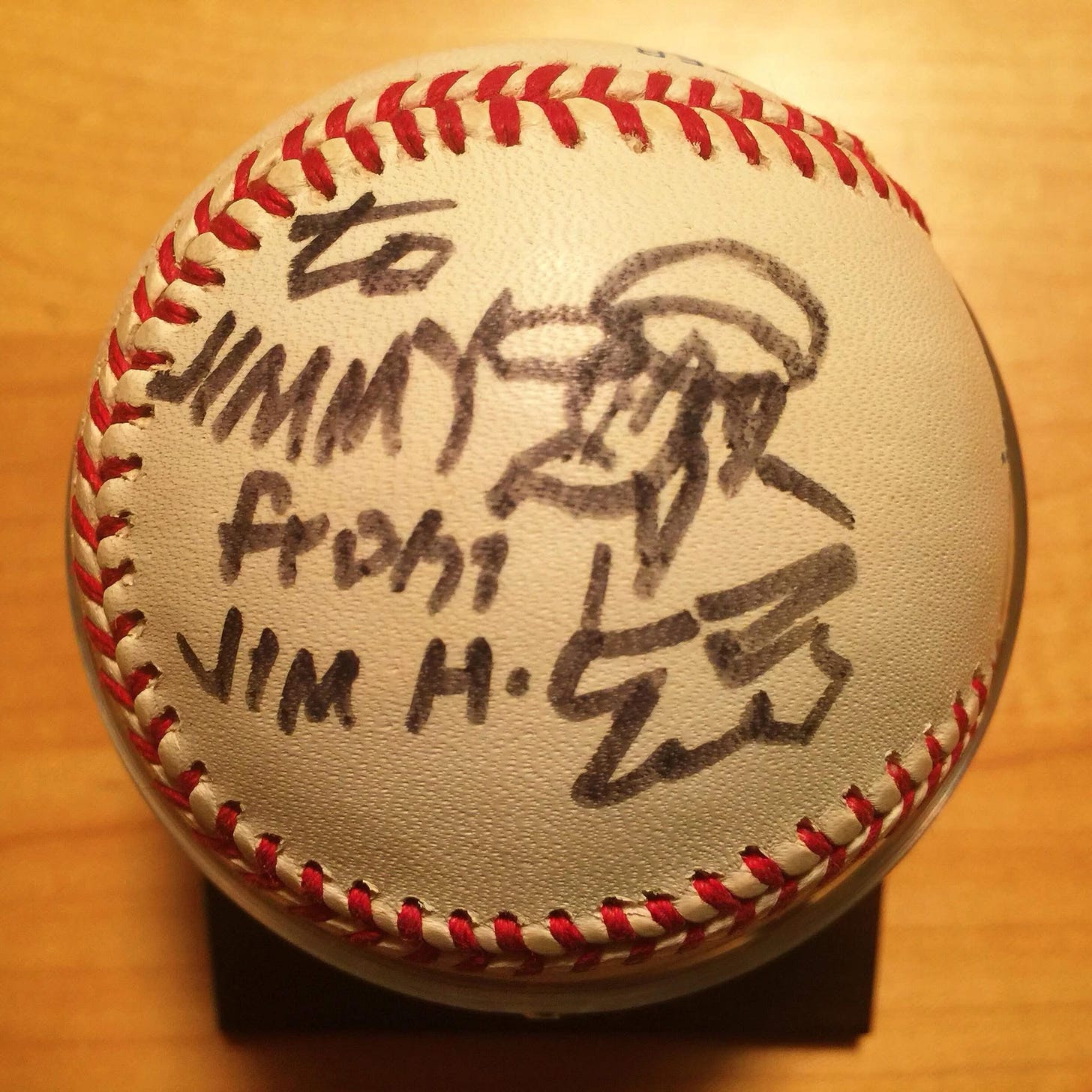

One day at a Towson game, Hartzell admired an 1890s Orioles cap worn by 11-year-old James Bigwood and struck up a conversation. Bigwood’s father recognized Hartzell, and at Towson’s next game, young Bigwood brought a ball and asked Hartzell to sign it. At age 91, Hartzell grabbed the ball and inscribed it, adding a sketch of his original Oriole bird.

Bigwood, who now works at the Maryland State Archives and subscribes to the Bird Tapes, still has the ball.

(Note from John Eisenberg: This post about the birth of the Oriole Bird owes its existence to Bob Golon, a retired manuscript librarian and archivist at the Princeton Theological Seminary Library. Upon hearing about the Bird Tapes, Golon contacted me about Armstrong, suggesting him as a topic to write about. A baseball historian and member of the Society for American Baseball Research, he authored the SABR profile of Armstrong and also sent me many of the images in this post. Golon is the author of “No Minor Accomplishment: The Revival of New Jersey Professional Baseball,” published in 2008 by Rivergate Books /Rutgers University Press. James Bigwood, both father and son, also contributed images to this post as well as the wonderful story about interacting with Hartzell at a Towson baseball game.)

Thank you for this wonderful article about my father and Jim Hartzell’s collaboration in creating “Mr. Oriole.”

Thanks for writing this post about the fascinating history of the Oriole Bird and especially the first Oriole bird —Jim Hartzell’s. I always Jim’s bird in various programs, yearbooks, scorebooks, stationary or memorabilia but especially on page one of the Baltimore Morning Sun. I wrote a short article about Jim’s Bird in the Baltimore chop last year.