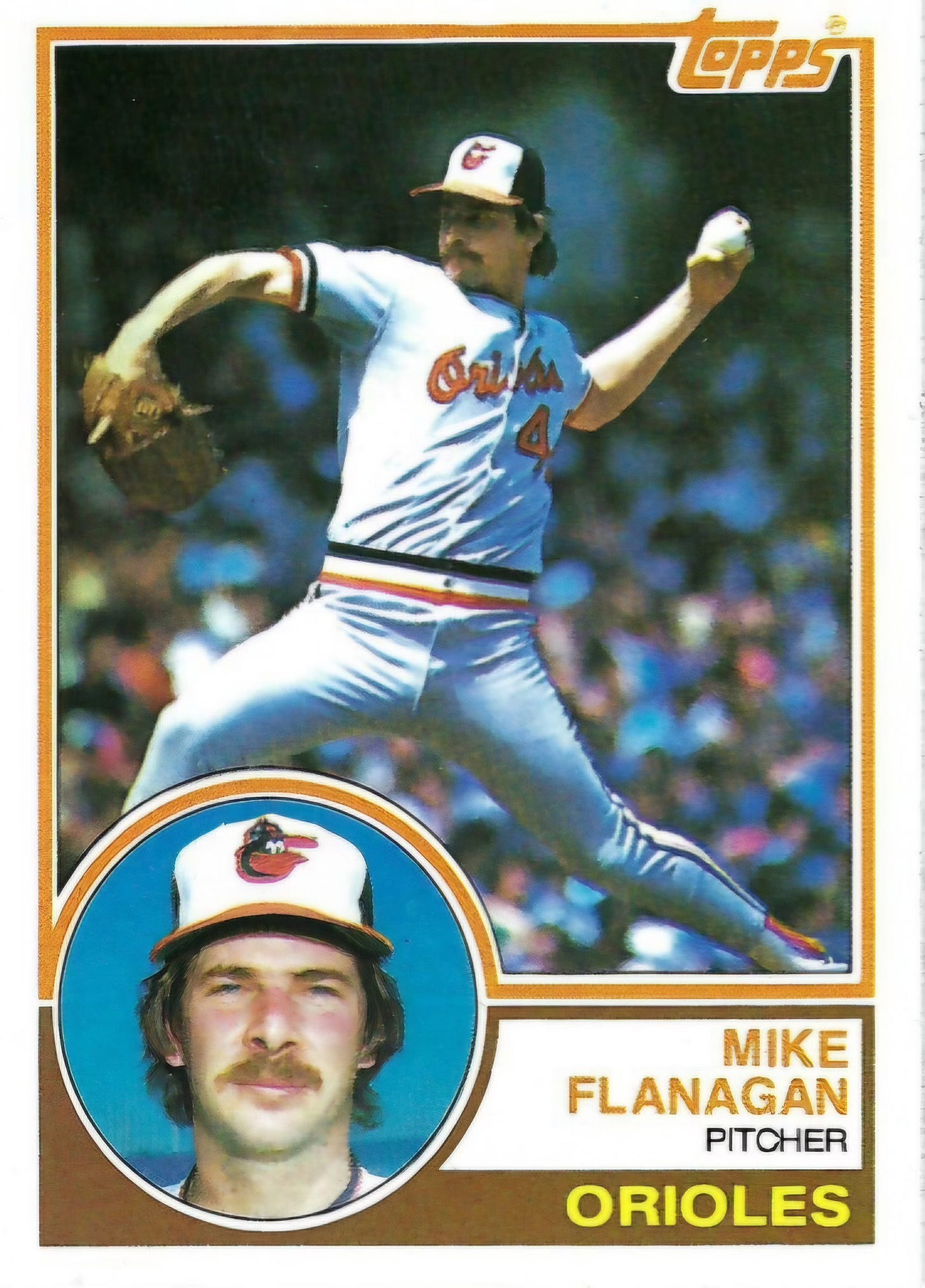

From the Archive: The Mike Flanagan Interview

My vintage interview with him outpolled four Hall of Famers in the Bird Tapes Holiday Gift Contest final voting. Our conversation from 1999 is posted below, available to all subscribers.

When I came up with the idea of letting Bird Tapes subscribers vote on which vintage Oriole interview they wanted to hear as a holiday gift, unlocked and free to all, I expected the winning subject to be someone with a statue at Camden Yards.

A Hall of Famer. The Orioles have plenty.

Sure enough, after the first round of voting in the March Madness-stye bracket elimination event, there were four Hall of Famers among the five finalists — Brooks Robinson, Frank Robinson, Jim Palmer and Earl Weaver.

But in the final round of voting, which concluded Saturday, the winner was the one non-Hall of Famer among the five finalists — Mike Flanagan.

The 1979 American League Cy Young Award winner received 33 percent of the vote in the final round. Brooks Robinson and Earl Weaver tied for second, each receiving 23 percent.

The people have spoken. My interview with Flanagan, recorded in 1999, is available below, unlocked and free to all subscribers.

It’s a good choice.

Full disclosure, I wrestled with how to handle my vintage interview with Flanagan, whose death at age 59 in 2011 rattled Birdland like few events in Orioles history. I feared that hearing him might upset some people or somehow seem inappropriate.

But once I listened to our conversation from a quarter-century ago, I felt my path forward on the matter was clear. When we spoke about his career and his era of Orioles history in the clubhouse at Camden Yards in 1999, the qualities that made him so beloved were fully evident. He was expansive and witty, a superb historian. Among the nearly 100 interviews I conducted for From 33rd Street to Camden Yards, my book on Orioles history published in 2001, none was better at distilling what made the Orioles so special for so long.

The Bird Tapes collection would be incomplete without my conversation with Flanagan, which presents him at his very best .

After joining the organization as a seventh-round draft pick in 1973, he learned the tenets of the Oriole Way at the lowest levels of the minor leagues, believed those tenets, preached them, understood them and was proud beyond measure of the winning force they generated on the diamond.

Throw strikes.

Catch the ball.

The importance of a single out.

Play smart.

Let the other guys lose the game.

Decades later, it’s almost funny to hear others boil down the Orioles of his vintage (late 1970s and early 1980s) to the three-run homers Weaver liked so much. Those were important, but the Orioles won year after year in that era because they were smart, sound, pitched well, played together, knew each other, liked each other, bonded over dealing with Weaver’s furies (“the time bomb in the dugout,” Flanagan called him) but also understood that Weaver made it all work.

They won a World Series after Weaver left and just before the machinations of free agency changed the nature of the game, making it impossible for a core to remain together for as long as theirs did.

Everyone plays a role in such a collective, on and off the field. Flanagan was the poet as well as a pitcher. Listen to him explain how the heart of their collective was the rollicking camaraderie found on the bus taking them to and from games on the road. There was just one bus, with everyone crammed on. Weaver sat in front, like a general leading his troops. The guys in the back, by the toilet, doled out insults and praise.

They rode together day after day, year after year, culminating with their rollicking ride from Philadelphia back to Baltimore after they won the World Series in 1983.

It couldn’t last forever, and it didn’t. Players from other organizations filtered in, including what Flanagan called “some non-believers.” Flanagan himself left, traded to Toronto. Ralph Salvon, the team’s loyal and beloved trainer, passed away. When Flanagan rejoined the Orioles in 1991 for a second act as a relief pitcher, there was no longer a single bus. The coaches and manager traveled separately from the players to and from games.

It spoke volumes. The era was over.

In our interview in 1999, Flanagan barely discussed the 141 career victories he recorded over 15 seasons in Baltimore or the Cy Young Award he won in 1979. But he talked on and on about the bus.

Although other players with more luminous records wore the Orioles’ uniform at Memorial Stadium, it was fitting that Flanagan was called upon to throw the last pitch at the ballpark in 1991 before the team moved to Camden Yards. No one who’d worn the uniform was better at articulating why the ballpark and its era of baseball evoked such powerful memories for so many.

He was a delight as a player, coach, broadcaster and executive over nearly four decades with the organization. A year after he took his life, his wife told Dan Rodricks, my former colleague at The Baltimore Sun, that he had battled depression for years. (Rodricks and Flanagan were fishing buddies.) It complicates remembrances of him, but my aim in posting our vintage interview is, simply, to honor the star he was and his singular contribution to the chronicle of Baltimore baseball history.

BIRD TAPES STOCKING STUFFER SPECIAL: In case you missed my announcement last week, gift subscriptions to the Bird Tapes are on sale at 50 percent off through Christmas Eve. It’s a great solution if you’re still wondering what to get an Orioles fan for the holidays. Annual and monthly subscriptions are also on sale at 50 percent off through Christmas Eve, so you can give the Bird Tapes to yourself if you want. A paid subscription gives you access to my entire archive of vintage interviews with former Oriole players, managers and executives. Click on the “subscribe” button below to access the discounted subscription options.)

Here is the interview:

Starting Part 1, Flanagan explains how he learned the value of teamwork while playing in the Orioles’ minor-league system in the mid-1970s. An umpire helped calm him down when he made his major league debut in 1975. He moved between Baltimore and Triple A Rochester a few times before establishing himself. Mike Cuellar worked with him even though Flanagan was there to take Cuellar’s job, a gesture he never forgot and later sought to emulate. That didn’t happen on other teams, Flanagan said. Jim Palmer helped calm Earl Weaver down when Flanagan started slowly in 1978 and the manager became impatient. The Orioles’ enormously successful pitching philosophy was built around starters going nine innings, relying on their fastball early and mixing in other pitches later.

Here is Part 1:

After the Orioles lost the 1979 World Series in seven games, it was frustrating for them to continue winning without reaching the playoffs in the early 1980s. That frustration ended in 1983 when the Orioles’ core had been together for nearly a decade and was hellbent on going all the way. It was a smart, resourceful core that knew how to win and have fun doing it. Weaver was tough to play for but he’d pull five games a year out of his hat. Showing they could win without him was part of the players’ inspiration in 1983. The American League Championship Series with the White Sox was the real challenge of the 1983 postseason, more than the World Series with the Phillies. The players thought they’d win forever but things began to change in 1985 and 1986. Some new players who came to Baltimore were non-believers in the Oriole Way. Flanagan tried to mentor his successor as the left-hander in the rotation, Jeff Ballard, but found Ballard reluctant. Being traded to the Toronto Blue Jays in 1987 rejuvenated him. Returning for a second act in Baltimore in 1991, he made the roster as a relief pitcher on a day he thought he was ready to walk away.

Here is Part 2:

Flanagan opens Part 3 recounting his version of the last game in Memorial Stadium in 1991, when it fell to him to throw the final pitch, effectively summing up everything that had transpired at the ballpark over 37 years. It was one of his greatest moments in baseball, but, he says, it also was a selfish moment. The Oriole Way couldn't continue at Camden Yards, he says. Playing for Weaver was a constant test of your mental toughness. The players bonded over their efforts to try to handle him. The environment around the team had changed when he returned in 1991. Before then, the team traveled to and from games on one bus on the road and it was a scene of humor and bonding. When he returned, the coaches and manager took a different bus from the players and the bonding exercise no longer existed. To Flanagan, the change symbolized what was right about the Orioles for so long, and how the game itself had changed, making it hard to sustain what existed in Baltimore for so long.

Here is Part 3:

Thank you. Did he ever talk about 1979? I had his 1979 card in MLB Rivals (a free game on Steam) and just went ham on upgrading it XD

ONE ORIOLE I WANT is B.J. Ryan or Brian Roberts.

I met Brian in '06 and we got a picture taken together. He had 50 doubles. I wonder if that was his goal or it just happened to be a condience that he would get that high.

For B.J. Ryan. He wasn't terrible. Just on teams that...really didn't give him anything to go off of. I got his 2002 card in MLB Rivals. Not sure if that was his best year BUT I could be wrong. I also went ham on upgrading the card XD

Sorry for the long comment. I figured I put my request in if you do them. You already finished the book but we are always cats right? Thanks John

It felt personal when Mike died. Having been treated for depression most of my adult life I only wish that he had found the right help. His final act meant he was unwilling to stand the pain any longer. He was loved by so many O's fans!