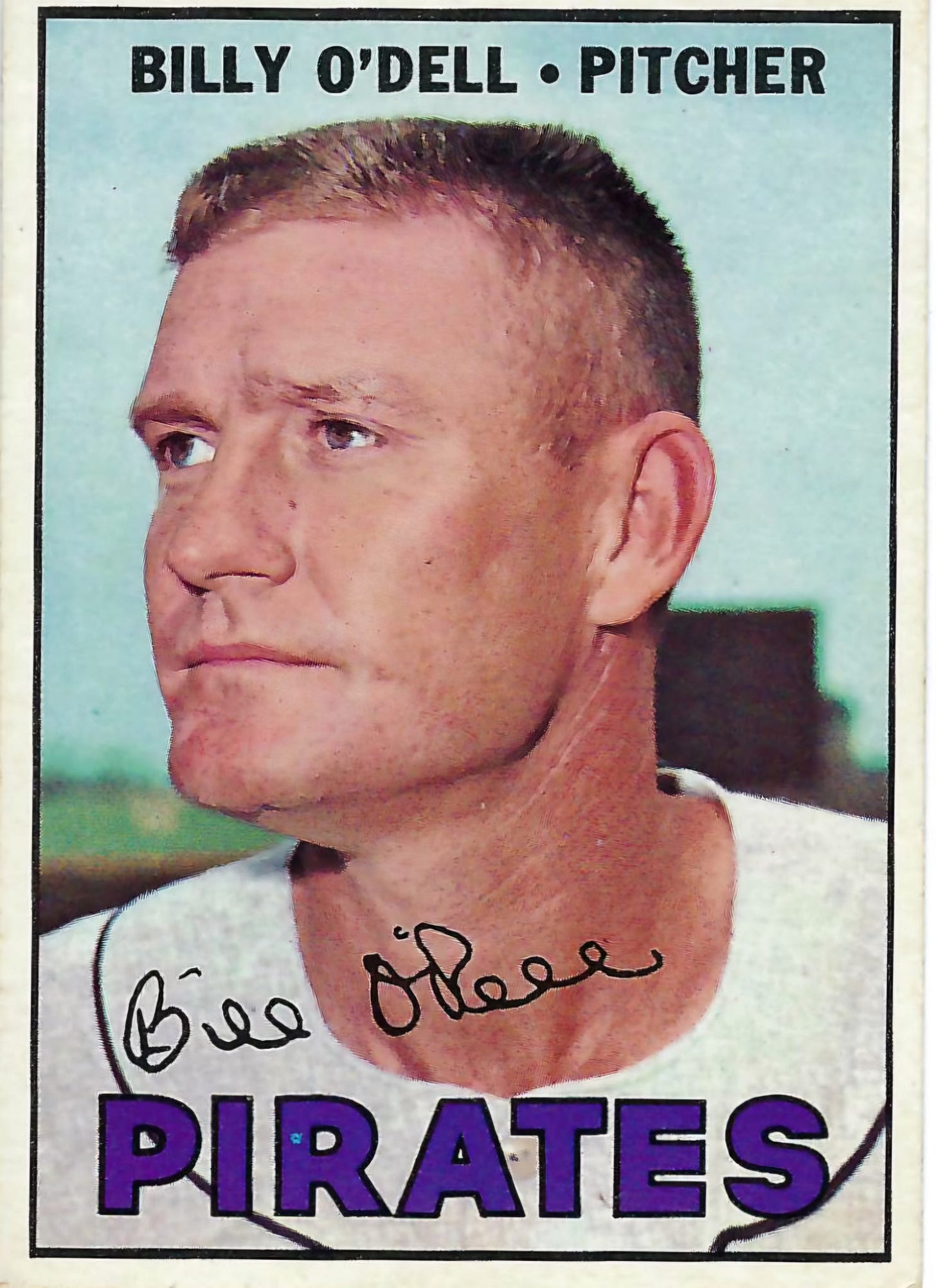

Classic Card: Billy O'Dell, 1967

The Orioles' inaugural bonus baby, he was the surprising star of Baltimore's first All-Star Game. Traded away when the club thought it had better pitching, he had success elsewhere.

Four years after they arrived in Baltimore, the Orioles hosted the All-Star Game before a packed house at Memorial Stadium on July 8, 1958. High on the list of the greatest sports events ever played in Baltimore, it featured a slew of future Hall of Fame inductees such as Willie Mays, Hank Aaron, Mickey Mantle, Ted Williams, Stan Musial, Ernie Banks, Yogi Berra, Al Kaline and Warren Spahn.

Safe to say, Baltimore has never hosted another game like it.

But as the fans exited the ballpark after the American League’s 4-3 victory, the player foremost on their minds was a relatively little-known Orioles pitcher named Billy O’Dell.

A diminutive 25-year-old left-hander from South Carolina, he was in his first year as a full-time Oriole in 1958. Deployed as a swingman by manager Paul Richards, O’Dell had an 8-9 record with four saves at the All-Star break. Those weren’t standout numbers, but his 2.96 ERA reflected an ability to get batters out, and the Yankees’ Casey Stengel, managing the American League, put him on the team at least partly to honor the unwritten rule of throwing a bone to the All-Star Game host.

O’Dell spent the first six innings of the game in the bullpen, his chances of pitching seemingly diminishing. But after the White Sox’s Billy Pierce reported that his arm felt tight while warming up, Stengel asked O’Dell to pitch the top of seventh.

Years later, when I interviewed him for my book on Orioles history, O’Dell vividly recalled the reaction he generated when he left the bullpen after warming up.

“The fans went crazy when I walked in along the first-base line to start the seventh,” he said.

The same fans had booed Stengel moments earlier, in the bottom of the sixth, for pinch-hitting Yogi Berra for Orioles catcher Gus Triandos, who’d started the game and singled in two at-bats. But the American League scored a run in the bottom of the sixth to take a 4-3 lead, and now it was up to O’Dell to protect the lead.

He retired the side in order in the top of the seventh, with Mays among his outs on a routine groundball. Impressed, Stengel let him pitch the top of the eighth, which meant facing Musial, Aaron and Banks — a daunting challenge O’Dell met with two more groundouts and a strikeout.

“With each pitch I threw, the roars got louder and louder,” O’Dell told me years later. “I didn’t throw anything but curves and sliders, and my control was good.”

Even though Stengel had more than a half-dozen other top pitchers available, he let O’Dell take the top of the ninth. The American League still had a 4-3 lead. The National League sent up Frank Thomas, Bill Mazeroski and Del Crandall. O’Dell retired them on a pop foul, strikeout and popup.

In Baltimore’e first All-Star Game, O’Dell earned a save, the game’s Most Valuable Player award and by far the loudest cheers.

“Four years later, I was with the Giants and Casey was managing the Mets, and he came over to me before a game, while I warming up,” O’Dell recalled. “I was wondering why he was coming over, and he said, ‘Mr. O’Dell, I never had a chance to thank you for that job you did for me in the ‘58 All-Star Game.’”

With his confidence buoyed, O’Dell pitched well down the stretch in 1958 and finished with a 14-11 record and 2.97 ERA. Having thrown 12 complete games in 25 starts, he appeared ready for a spot in Richards’ rotation.

“He has everything – speed, curve, control, confidence, courage and competitive fire,” Richards told reporters during spring training in 1959, according to a Society of American Baseball research profile of O’Dell.

It was just what the Oriole had envisioned when they made O’Dell their inaugural bonus-baby signing after his junior year at Clemson in 1954. Although he lacked commanding physical stature, he commanded a mix of pitches.

The bonus-baby designation, achieved because he’d signed for more than $4,000, meant he had to spend his first two years as a pro in the majors.

“I reported in June (of 1954) when the club was in Boston,” O’Dell recalled. “I was 21 years old and scared to death. Weighed about 152 pounds. (Orioles manager Jimmy) Dykes was an old school thinker. He thought you had to weigh 200 pounds and have five years of experience. I sat around until August.”

After making a few appearances in 1954, he disappeared for several years while in the military. When he returned in 1957, he posted a 4-10 record, raising doubts about whether he’d become a useful major leaguer. But Richards, a renowned pitching expert, worked with him.

“He talked to me a lot about pitching. He was always talking to me about changing speeds, which I did a poor job of at that time. He was always after me,” O’Dell said.

In the wake of his 1958 All-Star Game performance, he pitched well again for the Orioles in 1959. Even though he had a losing (10-12) record, he compiled a 2.93 ERA over nearly 200 innings and made the All-Star team for a second straight year.

After that season, though, the Orioles traded him to the San Francisco Giants in the deal that brought outfielder Jackie Brandt to Baltimore. The Orioles suddenly were awash in young starting pitching as Milt Pappas, Steve Barber Jerry Walker, Jack Fisher and Chuck Estrada developed, forming what would become known as the Kiddie Korps rotation, which helped the Orioles become contenders for the first time in 1960. O’Dell, who didn’t throw as hard, was deemed expendable.

But O’Dell had a lot of good years left when he departed Baltimore. In fact, he lasted longer and accomplished more in the majors than several of the Kiddie Korps stalwarts.

With the pennant-winning Giants in 1962, he went 19-14 with 20 complete games (that’s right, 20) and appeared in three World Series games, starting one. In 1963, he went 14-10 and logged 222 innings.

“I didn’t do a good job of changing speeds until after I left Baltimore,” O’Dell said.

In the latter part of his career, he pitched effectively but mostly out of the bullpen for the Milwaukee/Atlanta Braves and Pittsburgh Pirates. Pictured on the Topps card at the top of this post, he is near the end of his career yet still drawing praise for his low ERA. He retired with a 105-100 career record and a 3.29 career ERA, the latter figure reflecting what was consistently true about him:

He could get batters out.