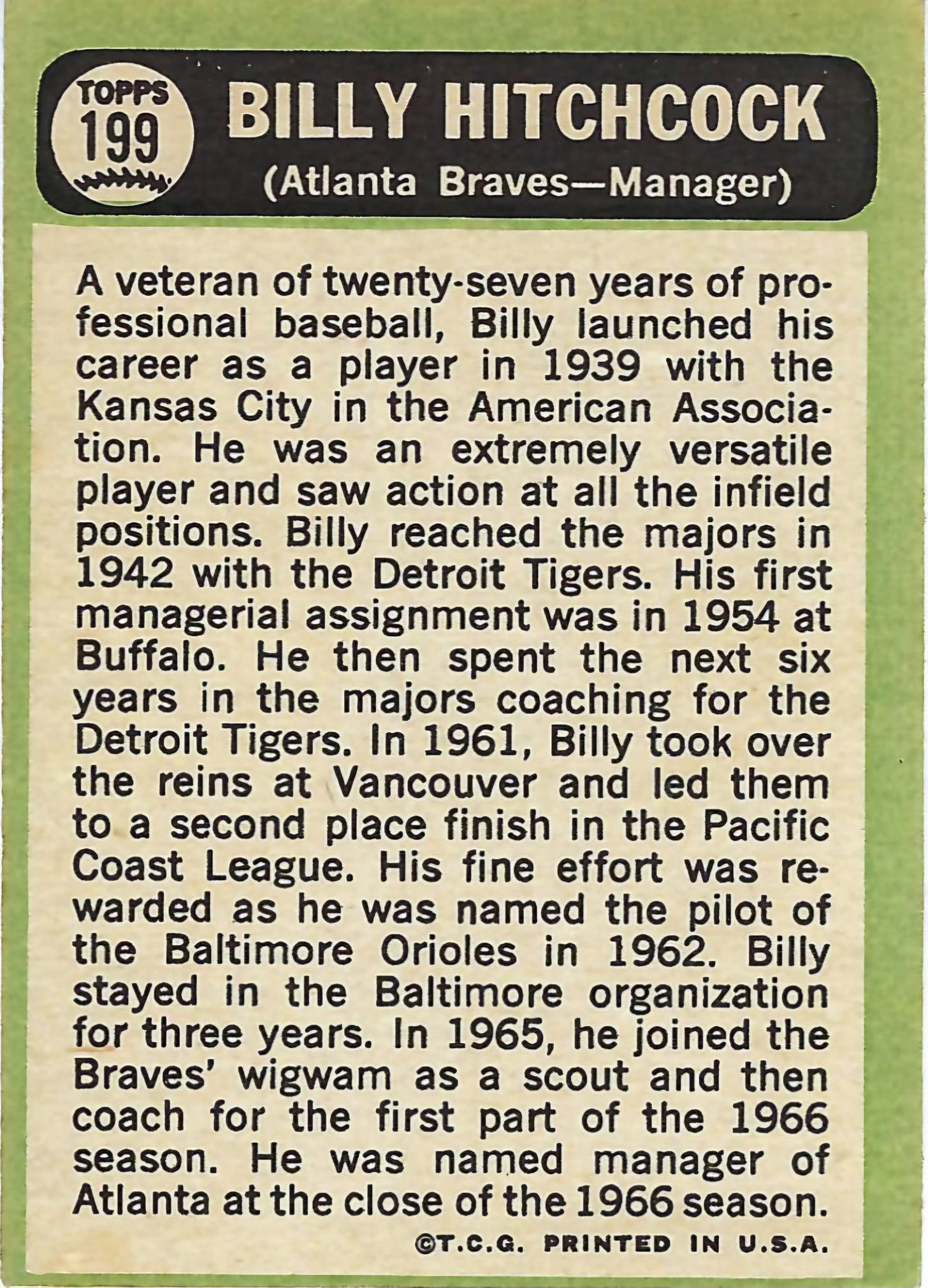

Classic Card: Billy Hitchcock, 1967

His brief shot at managing the Orioles was a disaster, but even that couldn't turn the courtly Southerner's smile into a frown.

That’s a grin, isn’t it?

Billy Hitchcock’s smile is so genuine and infectious on his 1967 Topps card that it’s hard to look at the card without breaking into a broad smile yourself.

It’s a card that says everything about the person on it. Hitchcock was a courtly Southern gentleman from Inverness, Alabama, a baseball and football star in the ‘30s at what is now Auburn University. Through his decades-long run in baseball as a player, manager, coach, scout and league president, he never failed to impress with his approach to being in the world.

“Billy was a hell of a man and a hell of a nice guy,” Orioles pitcher Milt Pappas said in his Bird Tapes interview.

It was for that reason that then-Orioles GM Lee MacPhail picked Hitchcock to manage the Orioles in 1962 after Paul Richards suddenly departed to oversee the launch of an expansion team in Houston. Richards was a brilliant and original baseball thinker who’d done as much as anyone to build the Orioles into a contender, but he was an aloof, distant and somewhat stern figure who often communicated with his players through his coaches. The Orioles won 95 games in Richards’ final season in Baltimore in 1961, but MacPhail thought the team would benefit from having a manager who was easier to live with.

Hitchcock was, indeed, easier to live with — too easy, it turned out. MacPhail was dead wrong in thinking the team would benefit, as he admitted in a 1999 interview for my book on Orioles history.

“He seemed like an ideal guy. A wonderful guy. He just didn’t inspire the team,” MacPhail said. “Some managers have that ability. Billy didn’t. He just wasn’t tough enough with them. They didn’t respond.”

(Note from John Eisenberg: I have a recording of my interview with MacPhail, but it took place in a restaurant and there’s so much competing noise that his words aren’t discernible enough to play as a Bird Tape. Sorry. Frustrating.)

I also interviewed Hitchcock in 1999 for my book, and fully on brand, he agreed with MacPhail, taking responsibility for the debacle that unfolded in Baltimore.

“I was sort of easygoing with the players,” Hitchcock told me. “You can’t beat them or whip them. You can fine them, but that’s about it. I guess Lee felt I wasn't demanding enough. Too easygoing. But that’s the way I managed. When I played, I didn’t need to have a manager be tough on me. I was going to give 100 percent. But my approach to that situation wasn’t exactly right. It didn’t work.”

Coming off the 95-win season in 1961, the 1962 Orioles featured future Hall of Famers Brooks Robinson, Robin Roberts and Hoyt Wilhelm as well as Boog Powell, Jim Gentile, Steve Barber and Pappas — the outline of a contender, for sure. But they regressed badly under the new manager, winning just 77games.

“The inmates were running the asylum,” outfielder Barry Shetrone pointedly told me in his Bird Tapes interview. “Everyone had been afraid of Richards and Hitchcock was very laidback, didn’t say much, and everyone went wild, like they’d gotten out of prison. It was crazy. A wild time. People playing cards right up to game time. No discipline at all. And quite a bit of drinking was going on. Billy was just put in a difficult situation, coming into an organization where he didn’t know the players, didn’t know what to expect. He was just too nice a guy for the job.”

Hitchcock told me, “Some guys might have taken advantage of me. I could see it. It was happening. But I couldn’t be a Joe McCarthy or a Paul Richards. I had to be me. But in this case, being Billy Hitchcock wasn’t the right thing.”

Overseeing such an immediate collapse can cost a manager his job, but MacPhail gave Hitchcock another chance in 1963 and the Orioles fared better. They were in first place at the end of May and ended up winning 86 games. Still, MacPhail had seen enough. He gave Hitchcock another job in the organization in 1964 and hired a new manager — Hank Bauer, a former Marine who’d earned a handful of World Series rings with the Yankees. The Orioles won a World Series in Bauer’s third year on the job.

By then, Hitchcock had departed Baltimore for a job with the Braves, who’d moved from Milwaukee to Atlanta, near where he lived in Opelika, Alabama. He started out as a scout but took over as the manager of the major league club after the All-Star break in 1966. This time, his easygoing approach worked and the Braves finished strong, convincing the club to keep him on as the manager in 1967.

Thus, we have the pleasure of seeing the card at the top of this post.

After the Braves won 77 games in 1967, Hitchcock announced his retirement. Within a few years, he was the president of the Southern League, a Double-A minor league circuit. In 1997, the baseball stadium at Auburn was renamed Hitchcock Field — a high honor certainly not based on his record as a major league manager, but rather, on the fact that he was a very nice guy.