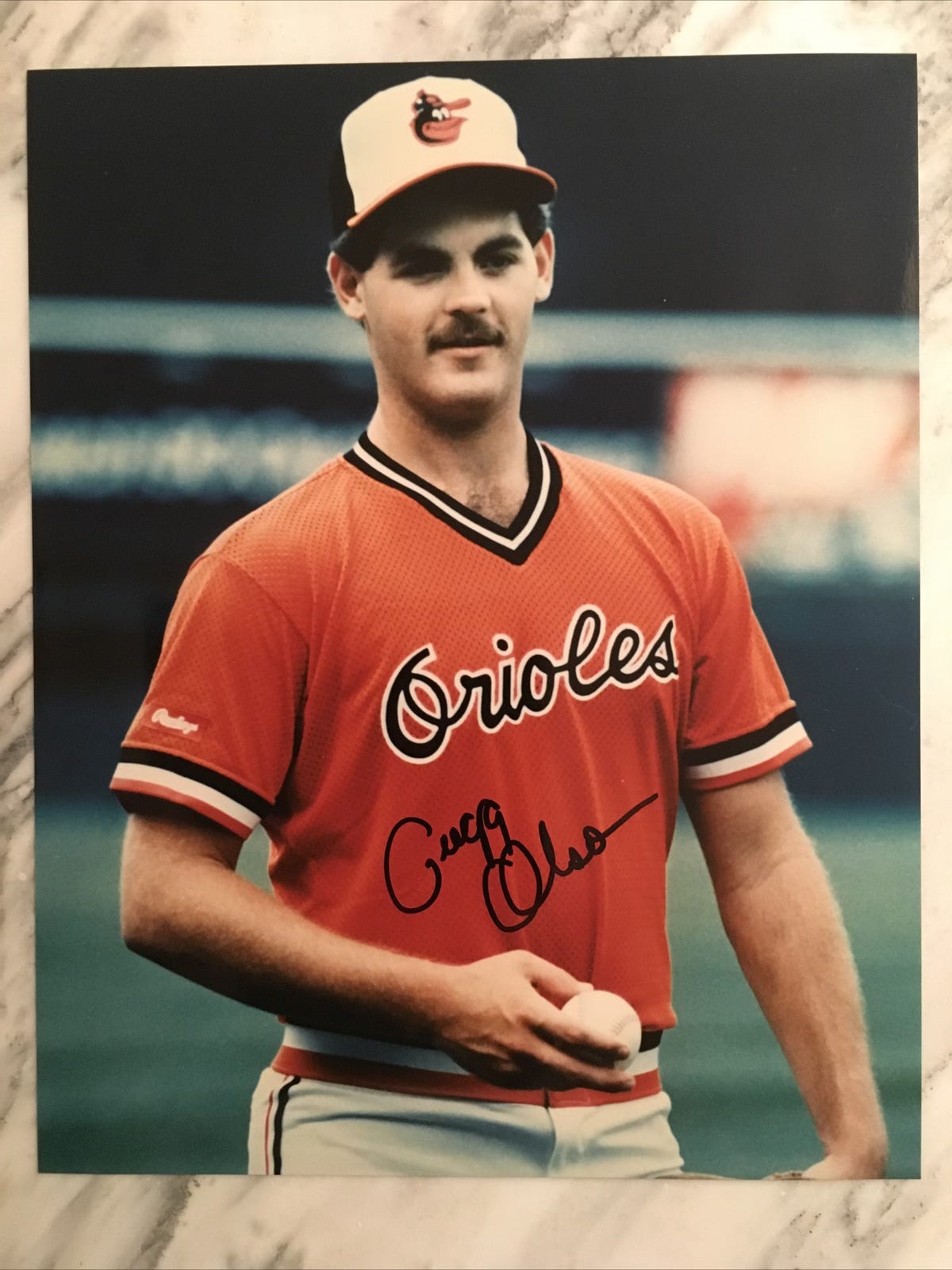

Bird Tapes 2025: An Interview with Gregg Olson

The Orioles' career saves leader described his pitching style better than I ever could: "A lot of loud noise." It made him a star before his divorce from the Orioles, which still bothers him.

The Orioles were truly a pitching superpower between 1963 and 1984, producing 24 20-win seasons from 11 different starters. Of course, the run couldn’t last forever. And boy, it didn’t. By the mid-to-late ‘80s, opponents were battering pretty much everyone Baltimore put on the mound.

On one especially miserable night in Toronto in 1987, Oriole pitchers yielded 10 home runs. A year later, Baltimore’s staff posted a 4.54 ERA, the highest in the major leagues by a good margin, during a season in which the team lost 107 games.

Gregg Olson’s ascendance as a 22-year-old rookie in 1989 sent a message to the rest of the majors, Baltimore’s beleaguered fans and perhaps even some in the Oriole organization itself. The message? Quite simply, all wasn’t lost. Confounding American League hittters with a searing fastball and just about the wickedest curveball anyone had ever seen, Olson demonstrated that the Orioles weren’t entirely out of the business of producing elite pitchers.

He represented a different spin on the premise of a Baltimore pitching star, as he wasn’t a 20-win starter, but rather, a vital reliever, charged with navigating the final innings of close games. It was a job that major league teams were just learning to value — the closer — and Olson gave the Orioles one of the best. Between 1989 and 1993, he appeared in 310 games, recorded 160 saves and pitched to a 2.15 ERA.

Even though a succession of top closers such as Randy Myers, Lee Smith, B.J. Ryan, Jorge Julio, Jim Johnson, Zach Britton and Felix Bautista has followed him in Baltimore, Olson is still the Orioles’ all-time saves leader — quite a feat when you consider he only played for the team for five full seasons. (Britton is second on the all-time list with 139 saves.)

But a recounting of Olson’s statistics, as impressive as they are, doesn’t convey what it was like to watch him. Contorting his body to put his full effort into every pitch, he threw two pitches violently hard — a 95 mph fastball that popped the catcher’s glove and a majestic curveball that broke like a rainbow crashing hard to earth, starting at 12 o’clock and ending at 6 o’clock and leaving batters either too mystified to swing or so frustrated after they’d missed that they slammed their bats in the dirt.

He was, in a word, electric.

Looking back on his heyday during our recent conversation, which is available below to paid Bird Tapes subscribers, Olson provided what I thought was a wonderfully succinct description of his pitching style:

“A lot of loud noise.”

Yup, that’s what it was.

And with that noise came his daring and unconditional approach to utilizing it. Take something off to play it safe? Olson didn’t believe in that. He trusted his stuff and deployed it at full throttle at all times. If it produced more walks than he wanted on some nights, well, he believed his stuff was good enough to bail him out of whatever trouble arose.

Now 58, he works as a college baseball analyst for ESPN and the SEC Network and teaches broadcasting at Auburn, where he first began to develop as a closer in the ‘80s. A native of Omaha, Nebraska, he was always an interesting and insightful player to interview — I wrote my share of columns about him in my years at the Baltimore Sun — and he hasn’t lost his stuff in that regard.

“I would have been real good in today’s game,” Olson told me.

Indeed, with his focus on maximum effort and velocity at all costs, he was years ahead of his time. These days, pretty much all teams care about how is hard you throw.

“I was the same as they are today. Everything I threw was as hard as I could throw it,” he said.

The start of his career was nothing short of fabulous. He saved 27 games and was voted the American League’s Rookie of the Year in 1989 as the Orioles surprisingly challenged for the AL East title. (As he recounts in our interview, he hasn’t forgotten the wild pitch he threw that proved pivotal in a key loss late in the season.) In 1990, he saved 37 games and made the All-Star team. In 1992, the Orioles’ first year at Camden Yards, he had 36 saves with a 2.05 ERA.

Yes, he had a few off nights, as all closers do, and there were times when he had to switch off his car radio on his drive home because he was tired of hearing himself get savaged on the postgame talk shows. (That was a tough business and it left a scar. I thought he would laugh about one of my favorite memories of him — the day he responded to blowing a save on “Turn Back the Clock Day” at Memorial Stdium by stuffing his vintage ‘66 Orioles uniform in a trash can. But as you can hear in our interview, he didn’t think it was so funny.)

But big picture, Olson sailed along with few hiccups until a big one arose — a partially torn elbow ligament injury, suffered during the 1993 season. Trying to pitch through it at first, he fouled up his mechanics. Then he was shut down shortly after the All-Star break. During the ensuing offseason, the Orioles abruptly released him — a divorce that shocked him and still resonates in his mind as he described his current relationship with the club as “tense” and “weird.” And that’s even though he rightfully went into the Orioles’ Hall of Fame in 2008.

He recovered from the elbow injury, but wasn't nearly as successful in the second act of his career, a wandering journey through eight organizations, pitching mostly in middle relief, from 1994 through his retirement after the 2001 season. (He did have a last hurrah, saving 30 games for the Arizona Diamondbacks in 1998).

Looking back now, he sees his forced exit from Baltimore as a key ingredient in the brew of factors that caused him to become a journeyman. He could have continued to thrive in Baltimore, he believes, with Mike Flanagan as his pitching coach and bullpen coach Elrod Hendricks, a key supporter, whispering in his ear.

“If I was able to stay, it would have been beneficial to both sides,” he said.

But his contract was up after the 1993 season and he moved on and never re-signed with the Orioles again, all because he was furious with them for having ceased to communicate with him after he was injured in 1993.

“I thought it was disrespectful, he said.

But the sour ending doesn’t lessen the impact of his Baltimore years. He was the first headliner of a generation of young, homegrown pitchers who helped reverse the Orioles’ shocking pitching decline of the mid-to-late ‘80s. In 1989, 25-year-old Jeff Ballard won 18 games and 24-year-old Bob Milacki won 14 games. They gave way to Pete Harnisch, who would surpass 100 major league wins; Mike Mussina, a future ace and Hall of Fame inductee; and Ben McDonald, a No. 1 overall draft pick who manned a high spot in the rotation. Olson led the way, his rise from Auburn to a starring role in the majors demonstrating that, yes, the Orioles still knew pitching.

(Note from John Eisenberg: A paid subscription gives you access to my interview with Olson as well as the 38 other interviews in the Bird Tapes archive. If you’re a free subscriber, click on the “subscribe now” button to upgrade to a paid subscription.)

Keep reading with a 7-day free trial

Subscribe to The Bird Tapes to keep reading this post and get 7 days of free access to the full post archives.